_edited.png)

The 36th Division Archive

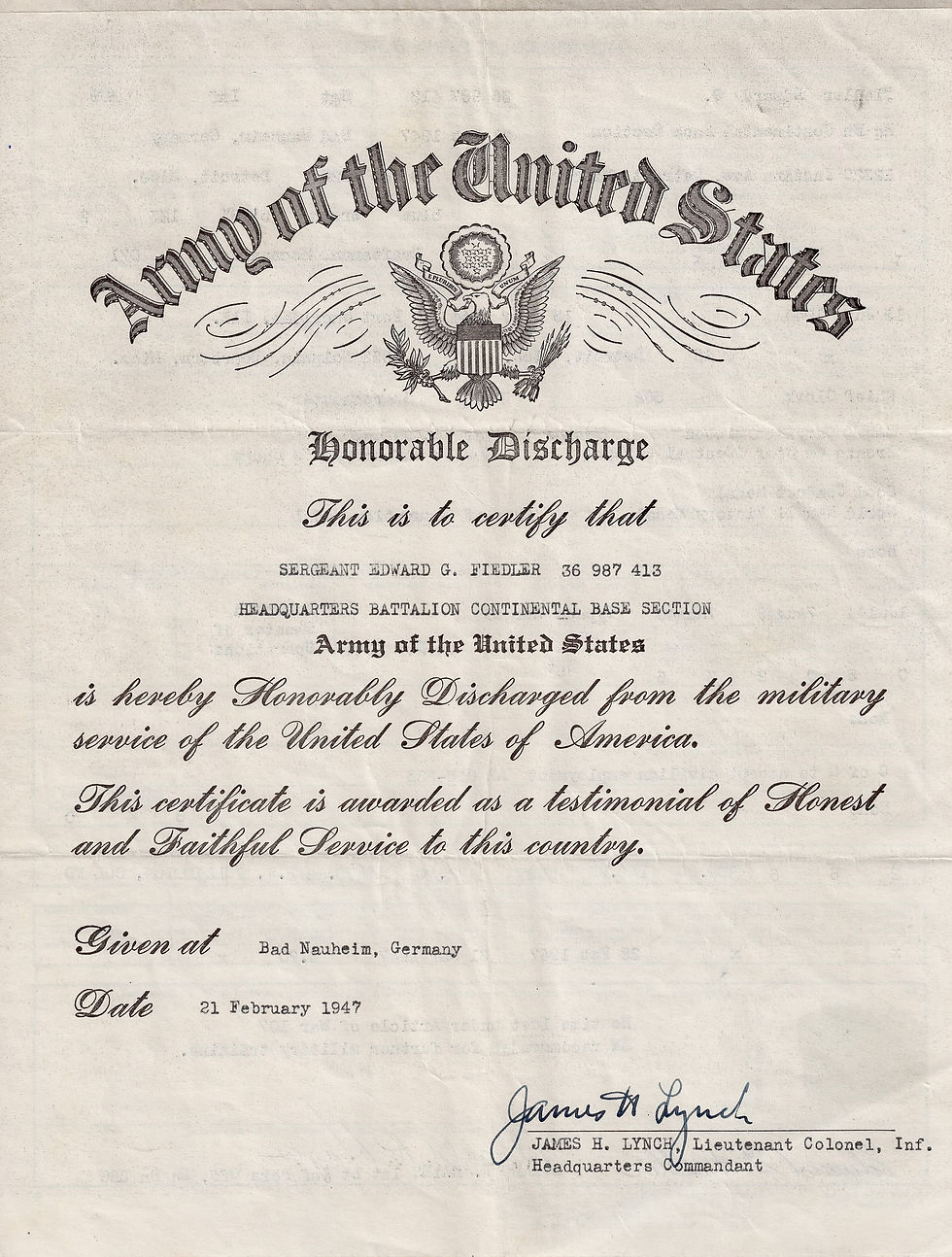

Sergeant Edward G. Fiedler

Rifleman

A Company, 141st Infantry Regiment

Edward G. Fiedler was born in February of 1920 in the Detroit suburb of Claytown. His father, a WWI veteran and drill presser for the Chevrolet motor company worked long hours in Detroit's industrial areas as Edward grew up and attended school. While in high school he began working part time as a draftsman under his father at Chevrolet and upon graduation in 1938, became full-time staff. A family built and sustained by Detroit’s booming motor industry, the Fiedlers were doing well for themselves by the time WWII began in December of 1941.

With war underway, the time for producing Chevys came to a halt as the GM factories retooled to begin producing weapons of war. Edward and his dad, both essential parts of the line, took part in this effort and began their own service to support the United States in the war. Despite making up roughly 2% of the US population at the time, Detroit’s industry produced over 10% of all wartime equipment, particularly the trucks, tanks, and vehicles of the GM plants like Edward’s. Despite this, the early war wasn’t all work and in October of 1942, he married his bride and began a family all his own. Less than a year and a half after, however, Edward’s position as an essential war worker was overridden by his youthfulness and he received a draft notice to report for duty in the United States Army, entering the service on 15 June 1944.

Edward’s first two weeks of service were spent at Fort Sheridan in Illinois where he spent the entire time going over basic discipline, drill, keep cadence, and how to carry a rifle. It was here that he met one of his lifelong friends, Harlan M. Hoffman of California, with whom he would see the war through. Upon conclusion of those first weeks, Edward and Harlan were shipped to Camp Wheeler, Georgia where they were put into an infantry company for three months of basic training. Wheeler became the true test for the draftees as they worked to master close-order drills, marksmanship, identification of enemy vehicles, gas procedures, and many other essential skills needed for life on the front. After graduation, the pair stuck together and moved to New Jersey where they boarded a troop ship bound for Europe on 15 November. Landing in England a week or so later, they moved to France and spent a few days in various “tent cities” before they got their final orders to join the 36th Infantry Division.

At the time of their entry, the 36th Division was in the middle of an intense war over the Vosges mountains in Central France. As they drove to their unit they both noted the countless devastated towns, burned-out tanks, and abandoned weapons dotting the French landscape as artillery thundered in the distance; solemn markers of the fierce fighting that had raged in the region for over two months. Officially attached to A Company of the 141st Infantry Regiment, the two green GIs likely had no idea of the recent history of their unit and the future combat that they would see. In the days prior to their arrival, the 36th had fought fiercely to capture the St Marie Pass, a critical pathway for troops and supplies through the Vosges that spilled onto the Alsatian Plain, the ultimate objective of the allied assault. The division faced stiff German resistance attempting to plug the gap and moved as many men as possible through the moment it was secured.

On the morning of 9 December, Edward and Hoffman were given a final ride on a jeep with two other replacements to join their company on the frontline. Immediately upon their arrival, the group came into chaos. The 1st Battalion of the 141st was pressing an attack on a series of ridges near the town of Riquewihr, a central point of the St. Marie Pass, and was undergoing severe German self-propelled gun and small arms fire. Within minutes the companies of the battalion had taken serious casualties but the attacks pressed on to maintain control over the objectives. After jumping off of their jeep Edward and the others were gathered by other men from A Company, told to turn in their rifles, and given red cross-painted helmets to replace their own. Although trained as riflemen, the severity of the fighting left many dead and wounded stranded on the battlefield and the group was told they would, for the foreseeable future, be serving as litter bearers to bring those injured back to a makeshift aid station. The cry of “medic, over here,” kicked the group into action only minutes later. For the rest of that first day, the makeshift medics dragged American and German wounded to safety without rest, saving dozens of lives. They were only given slight rest that night when the battalion retreated from their positions to move back towards the town of Riquewihr itself.

Officially replacing the 2nd Battalion in the town on the night of the 11th, the 1st Battalion was awoken in the early hours to the sounds of tanks and vehicles in the nearby hills. At 8:45 AM, all hell broke loose as the German 189th Infanterie Division, staffed by infantry, grenadiers, panzers, and mountain troops, launched a mass assault on the two battalions of T-Patchers holding the town and surrounding hills. With the primary objective of taking “Hohe Schwaertz,” or the large hill mass connecting the pass near the town, the 1st Battalion was attacked by a large detachment that snuck its way to the back side of the town using the forest as cover, reaching the outskirts before the GIs detected them. The fighting was ferocious, house to house, door to door, window to window, as Germans and Americans battled over the cobbled streets of the formerly quaint French city. Clerks, cooks, and supply troops all joined the fight as it became one for survival, only letting up after thirteen tanks of the 753rd Tank Battalion joined in to support the defenders. Edward and his crew were kept busy without rest as bodies littered the streets and the shouts of dying men rang throughout alleyways all across the town. The fighting over the small town continued for two more days as Edward, Hoffman, and the other replacements met their baptism of fire with a canvas litter rather than a rifle. They worked nonstop, day and night, only sleeping and eating when they had a moment available to them; lives were in their hands. The battle over the town ended on the 14th but the fighting in the surrounding hills continued for several more days as the regiment engaged in harsh combat to push back the determined German attackers. Edward’s group worked throughout the entire engagement and received no relief until the unit was relieved by the 3rd Infantry Division on 18 December, allowing them to join the rest of the division for a brief rest and light Rhine patrol duty before moving to reserve positions in January.

The month of January was mostly spent in defensive positions in northern Alsace, only restarting combat operations on the 29th. Edward, now a rifleman for his company, saw particularly difficult obstacles as his company maneuvered through a heavily mined and booby-trapped area as they advanced toward the town of Hagenau in pursuit of the Moder River. On 15 March the company crossed the crucial body of water but not before Edward’s best friend, Hoffman, was hit by an 88mm round that landed near his foxhole, only wounding but removing him from the line for the rest of the war. The advance across the river was met with little personal resistance, only scattered unitless clusters and the company noted seeing numerous legless and injured Germans abandoned in fields, injured by the mines they had been planting for the Americans only hours before. On the 20th the battalion began its “last great battle” according to Edward as the 1st Battalion took on the Siegfried Line defenses near Wissembourg. They were met by scathing machine gun and mortar fire, pinning them down until they were forced to retreat and regroup. Thankfully, the 142nd Infantry Regiment had better luck and Edward’s unit was able to cross the line at the gap they had made in Schweigen. Now alongside their foes, the battalion flanked the Germans north of Wissembourg, clearing the woods and taking 47 large pillboxes amongst dozens of smaller ones within a single day. By the 23rd the line had totally collapsed and the T-Patchers began the final drive into Germany.

Edward’s final days in the war were rather tame compared to the actions he saw in the Vosges. Most of April was spent riding atop trucks and tanks dozens of miles a day into Germany, heading towards Austria, as only scattered German resistance from collapsing armies sporadically opposed them. On 1 May Edward’s own company sent out a patrol that captured Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt, hero of the Eastern Front and defender of the Atlantic Wall. On 8 May 1945, the rest of the German armed forces surrendered and Edward’s six months of combat came to an end.

As a late draftee Edward was fairly low on the points needed to send a GI home, leaving him to spend two more years in Germany serving occupation duty with the 36th Infantry Division and 7th Army. In 1947 he was discharged from active duty and instead switched to a civilian personnel job with the adjutant general section of the Constabulary in Heidelberg where he worked in the exchange service. A few more years of work there saw him return home to a wife ready to divorce him, leaving him all alone in 1949. He spent several years attempting to settle and find a long-term job but the army seemed to keep calling him back, eventually leading him to move to Germany to work as a contractor, staying there until retirement and his passing in 2007.