_edited.png)

The 36th Division Archive

Staff Sergeant John Ybarbo

Squad Leader

2nd Platoon, K Company, 142nd Infantry Regiment

John Ybarbo was born on July 21, 1915, in the town of Goliad, Texas. Ybarbo was a Texan Tejano through and through. On his father’s side, his military heritage traced back to Texas’ earliest roots as his seventh great-grandfather, Matheu Ibarvo, was one of the first Spanish soldiers sent to Texas in the 1710s. For generations the Ybarbo family inhabited the towns of east Texas, including several serving with the Confederate Army during the Civil War. As with many Texas settler families, the Ybarbos married into Mexican families in the region, forming the rich Tejano culture many in Texas still celebrate today. Ybarbo’s mother had more recent Texas roots, as her father had only moved to Texas in the mid-1800s from Tamaulipas, Mexico. A number of Ybarbo’s distant relatives still remained on that side of the border, although most were in eastern Texas.

The CIB and ribbons are German-made and sewn to the uniform.

Ybarbo’s father, Leon, was a farm hand in Goliad. He managed to scrape by and provide for Ybarbo and his three siblings as they all attended school. Ybarbo was a bit of a troublemaker in his youth, causing trouble for his parents. His wife later recalled that during prohibition, his father kept a still which he used to make whiskey. Supposedly, Ybarbo liked to borrow the still and make beer which he would then sell to local middle-schoolers for spending money.

Times gradually grew tough in Goliad, so in the late 1920s the family moved to Victoria, Texas. Victoria was a small town but an avid hub of agricultural production in eastern Texas. Cotton, cattle, and rice farming formed the backbone of the economy as a diverse community of African Americans, Tejanos, Mexicans, and Anglos all worked its many fields.

Unfortunately, Victoria was also a very segregated town. City events and property were often off-limits to non-whites like Ybarbo. The city’s hispanics and blacks were left in segregated impoverished communities on the south side of the town. It was here that the Ybarbo family moved and lived off of Depot Street, just down the road from the city’s main segregated public school. By 1930, Ybarbo had left school to help make money for the family. He, his older brother Leon, and his father all began work as laborers on a cotton farm outside of town. While the Great Depression hit Victoria as hard as anywhere else, an oil boom kept its economy somewhat stable for the Ybarbos and other residents.

By January of 1941, Ybarbo had transitioned away from farm work and begun practicing carpentry with a local construction company since the city of Victoria was experiencing a growth spurt. He was still living with his parents and two sisters, however. At the same time, likely to supplement his income, he decided to enlist in the U.S. Army as a member of the Texas National Guard. He underwent his basic training at Camp Bowie and soon was assigned to 2nd Platoon, K Company, 142nd Infantry Regiment, 36th Infantry Division. Little did he know at the time, but this company would take him through the next four years of his life.

John Ybarbo, on left, with his older brother Jesus, on right.

Victoria, Texas in the 1940s

A Texas cotton field in the 1940s

John Ybarbo, on left, with his older brother Jesus, on right.

At the time of Ybarbo’s enlistment, the 36th Division had been federalized, meaning it was preparing for more active duties with the Army. That fall, Ybarbo participated in the Louisiana Maneuvers alongside the rest of the division before returning home. It was not long after that the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Only weeks later, the division was reorganized and Ybarbo was called up for full-time military service.

Ybarbo traveled with the 36th Division to Camp Blanding, Florida, the Carolina Maneuvers, and, finally, to Camp Edwards in Massachusetts in the fall of 1942. By this point, the 36th Division was more experienced and seasoned compared to other guard units. Camp Edwards brought with it more extensive training, signaling to the men that before long they would be shipped overseas. Camp Edwards was a uniquely special post for Ybarbo, however, as it was where he met and married his wife, Wilma. First meeting at an off-base party hosted by one of her friends, Wilma and Ybarbo hit it off and talked all night. It was “love at first sight,” according to Wilma. On January 2, 1943, they were married.

The war would not wait for the young couple, and in April Ybarbo shipped off with the division to North Africa where they would prepare for service in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations. From April to August the division remained in North Africa undergoing even further training, particularly in amphibious operations, as the men began wondering when they would finally see combat. During this period, Ybarbo’s son, Jimmy, was born back in the United States.

On September 9, 1943, Ybarbo entered into combat alongside the rest of the 36th Division, storming the beaches of Paestum to begin the liberation of Italy. K Company was within the first wave landing on Red Beach and throughout that first day the men attempted to push forward as far as they could in spite of heavy German tank attacks. The 3rd Battalion spent most of that first week defending several hilltops critical to the division flank. As the landing zone became secured, the division moved inland, supporting the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment at Altavilla before finally getting some time to rest.

36th Division troops at Salerno

36th Division troops at Salerno

It was not until mid-November that Ybarbo went back into the line, as the division relieved elements of the 3rd Infantry Division on Monte Camino, one of the main American positions along the German “Winter Line.” Artillery and patrols were constant during this period, mostly characterized by static defense in the rain, fog, and mud of the Italian mountains. In Early December the larger Allied offensive began in the Camino area, with Ybarbo’s battalion providing support for the First Special Service Force and Italian 1st Motorized Brigade while the other T-Patchers battled through the nearby town of San Pietro.

The end of the year was spent in the mountains as the division licked its wounds from the harsh fighting it had endured. The Italian winter remained quite miserable, subjecting the men to rain, snow, sleet, and endless mud. The 142nd Infantry was attached to II Corps and continued to hold Monte Sammucro while the First Special Service Force once again pushed through to lead the assault on the hill. Afterward, the regiment enjoyed a few weeks of rest before acting as division reserve during the horrible assault across the Rapido. It was during the crossing, on January 20, that Ybarbo was promoted to Sergeant and made a squad leader in K Company.

February saw 3rd Battalion primarily in a defensive role along Monte Castelonia, but the company still came under artillery fire daily while its patrols encountered scattered firefights with the enemy. During this time, a number of the men were given leave to the 5th Army rest camp at Caserta, including Ybarbo. Unfortunately, Ybarbo suffered severe injuries, likely from a car accident, including concussion, chest and rib fractures, and lacerations. He was taken to the 32nd Station Hospital on February 22 where he recovered until March 10. While recovering, K Company awarded him his Combat Infantry Badge and promoted him to Staff Sergeant.

Throughout March, April, and May, 3rd Battalion underwent a period of rest and training. Traveling around a few different spots in southern Italy, the entire division had a refresher on amphibious operations before receiving orders to travel to the Anzio beachhead in late May. On May 19, 1944, Ybarbo and the rest of the battalion loaded up on LCIs near Pozzuoli to head for Anzio, arriving the next day at 1130. The battalion unloaded and drove a few miles inland before occupying forward positions in anticipation of their orders to join the fray.

Some K Company men in Italy.

Ybarbo appointed as Sergeant.

142nd Infantrymen taking German prisoners to the rear.

Some K Company men in Italy.

The orders to join the attack on Rome came on May 31 as 3rd Battalion led the regimental rear during its large flanking maneuver through the 141st Infantry and up onto the peak of Monte Artemisio, a large ridge overlooking German soldiers defending the town of Velletri. While the 1st and 2nd Battalion of the 142nd Infantry flanked downward to attack the Germans, 3rd Battalion remained on the hillside in reserve, calling out German movements and sending combat patrols to ensure the regiment’s flank was secure. Before long, the Germans withdrew from the town entirely and ran back to Rome.

3rd Battalion led the 142nd Infantry’s drive from Velletri, taking dozens of German prisoners as the regiment moved through the hills just outside of Rome. After hearing Allied forces had entered the city, the men pressed onward, finally entering the “eternal city” on June 5, 1944. They advanced through the streets to cheering crowds and proceeded several miles north until ambushed by German machine guns, small arms, and anti-tank guns. K Company flanked around the German positions and launched a counterattack, killing fifty and capturing thirty. Tragically, however, K Company's commander, Captain Joseph F. Edelen, was severely wounded. Lieutenant Frank L. Beers took over.

Over the next several weeks the battalion chased German forces north, fighting a number of engagements in and around small Italian towns along the coastline. By June 26, 1944, the entire 142nd Infantry was relieved and sent all the way back to Naples, near where their many months of Italian combat began. July was yet another period of rest interspersed with additional training, this time in amphibious tactics for the division’s upcoming second invasion: Operation Dragoon.

Operation Dragoon called for three American divisions, the 3rd, 36th, and 45th, to land along the French Riviera and quickly break through the German defenders stationed in the southern regions of the country. This would open a new front in the fighting while supporting the advances made from Normandy. Ybarbo and the rest of the 142nd loaded up on August 10, setting off from the Italian coast on the 13th. Dinner was chicken and ice cream as the men were briefed on their upcoming mission.

142nd infantrymen on the move at Velletri.

142nd troops heading inland during Operation Dragoon

142nd infantrymen on the move at Velletri.

On August 15, 1944, Ybarbo set foot in France. Although the 142nd Infantry was originally planned to land on the beach next to the town of St. Raphael, German mines led the division commanders to abandon the plan and let the 142nd land alongside the other regiments of the division on Green Beach at Ia Dramont. 3rd Battalion hit the beach around 1430, loading up on tank destroyers and tanks at 1630 for the move towards Frejus, a coastal town, which was their initial objective. 3rd Battalion moved through 1st Battalion in the dark that first night, which was silent and still, as the men prepared for their first combat in France.

In the dark of the early morning, Ybarbo and his battalion attacked the Frejus. They first seized a military outpost known as Camp Gelliene, which was largely abandoned, before moving onto the edge of Frejus itself around 0410. German resistance emerged soon after as flares, small arms, machine guns, and mortars opened up at the road junction north of Frejus while part of the garrison from Camp Gelliene appeared to engage in a counterattack. Fighting was house to house throughout the morning, and tthe battalion took over seventy-five prisoners in the process. German tanks were spotted several hundred yards away but were driven off by the American M-10s of the 636th Tank Destroyer Battalion. By noon the town was largely secured, but 3rd Battalion spent several more hours mopping up pockets of resistance. 3rd Battalion's first objective in France was secured.

Around 1800, 3rd Battalion mounted again onto tanks and tank destroyers to move north along Highway 7, a main roadway going deeper inland. They did not travel far until a battery of German anti-tank guns opened fire on the column just south of Le Puget sur Argens, knocking out the leading American tank and causing the infantry to dismount and fight their way to the guns. In the ensuing firefight, two more American tanks were destroyed but the guns were eventually neutralized. 3rd Battalion had to rough it the rest of the night, marching into the town before bedding down in houses for the night.

Armor support for the 36th Division unloading at Ia Dramont, near St. Raphael.

An original battle map used by Brigadier General Robert Stack, assistant commanding general of the 36th Division, showing the locations and targets of the 36th Division landing zone in Dragoon.

Troops of the 36th Division offloading in Operation Dragoon.

Armor support for the 36th Division unloading at Ia Dramont, near St. Raphael.

On August 17, 1944, Staff Sergeant Ybarbo, a well-seasoned veteran of Italy and the first days of Dragoon, performed an act of heroism that led to his first Silver Star Medal.

Around 0300, 3rd Battalion mounted up again on its armored transports and moved towards the town of Draguignan, dismounting at Trans and going by foot until it reached the city. Draguignan was the home of the German 62nd Corps headquarters. Paratroopers of the 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion had spent the last day fighting over the town, but another 500 or so German remnants had moved northwest to a villa, Chateau du Salles, alongside the corps commander, all refusing to surrender. 3rd Battalion was sent to find this group, flank them, and break their defense.

The battalion moved out at 1400, heading east up a large ridgeline which dominated the town. American artillery began firing on their target at this time, but the battalion had to traverse through thick woods before they finally reached the initial point of their attack. Unfortunately, they got lost briefly, and suffered a short delay. Sometime a few hours later, the battalion began moving down the hill towards the position of the German troops and a large firefight broke out.

The Germans had spread out throughout the compound and nearby buildings, forcing the battalion to work its way through the fields and vineyards. K Company took up the reserve slot of the battalion during the attack, but they did not miss any of the action. While I and L Company were moved forward, a group of German troops tried to flank the battalion from the rear, forcing K Company to set up defensive positions. Ybarbo and 2nd Platoon sprung into action. Roy Christensen, one of Ybarbo’s company mates, described his actions:

His platoon was in the assault when a strong rear guard action forced his company to set up defensive positions. Sergeant Ybarbo’s squad tried to work to the rear of the enemy strong point to liquidate it. So old Johnnie swept up his squad to the rear of the enemy and worked into firing positions, but despite the strong base of fire that was built up, his platoon was unable to dislodge the Krauts. Then Ybarbo took off across an open field about 200 yards wide, leading his squad in a vicious assault… Old Johnnie ran across the field like a rabbit. He had guts.

Ybarbo’s official Silver Star Citation reads

John Ybarbo, 38026352, Staff Sergeant, Company K, 142d Infantry Regiment, for gallantry in action on 17 August 1944 in France. While the 2d Platoon of Company K was assaulting a well-organized enemy strong point, the attackers were pinned to the ground by heavy hostile small arms, mortar, and artillery fire. Sergeant Ybarbo was assigned the mission of leading his squad to the rear of the enemy position in order to relieve the pressure on the remainder of the platoon. He skillfully maneuvered the men to the left rear of the strong point and there built up a line of fire. When he realized that his squad’s fire power was insufficient to dislodge the well-entrenched enemy, Sergeant Ybarbo swiftly organized his men and led a bold and determined assault. Using his bayonet, rifle, and grenades in the intense fighting which followed, he alone killed three of the hostile soldiers, wounded two, and captured six prisoners. Although he was painfully wounded, Sergeant Ybarbo directed his men in overcoming the resistance, thereby enabling his platoon to continue its advance and achieve its objective. His gallant action reflects great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of the United States. Entered the Service from Victoria, Texas.

Thanks to Ybarbo’s actions, K Company was not overrun and a threatening German position was destroyed. 3rd Battalion pushed through the German defenders over the course of the next several hours, finally breaking the holdouts later in the evening.

The route taken by 3rd Battalion to the German stronghold on August 17, 1944.

The attack of 3rd Battalion on the strongpoint, where Ybarbo helped stop a German flanking attack and received his first Silver Star Medal.

Ybarbo in the August 1944 casualty list of the 142nd Infantry.

The route taken by 3rd Battalion to the German stronghold on August 17, 1944.

Ybarbo, unfortunately, suffered a fairly serious gunshot wound to his right arm in the process which required immediate evacuation. Because he suffered this wound only two days into the invasion, proper hospitals had not yet come ashore. Instead, he was taken to the 70th Station Hospital which was conveniently floating aboard the USAHS Weder just off the coast of St. Raphael with the rest of the invasion fleet. He did not leave the ship until September 8 when he transferred to the 7th Replacement Depot in order to slowly filter back to K Company. On September 23, he finally rejoined his comrades while they were in the midst of clearing Remiremont.

Remiremont, many hundreds of miles from Ybarbo’s last combat action, was a mid-sized town nestled in the southwestern Vosges. As American troops pushed the German forces of Southern France northward, they gradually fell back into the mountainous forests of the Vosges, in central France. Here they planned a series of defensive lines to hold up the speedy American advance. They would do so quite effectively. Remiremont was a central hub of the initial German line, hoping to keep the Americans on the western side of the Moselle River. When Ybarbo rejoined his company, the Germans had just abandoned the city and blown the last bridge across the Moselle. 3rd Battalion held the town in a defensive posture until September 25 when it was able to ford the Moselle on trucks, thanks to a crossing site found by the 141st Infantry Regiment.

Unlike the long, relatively flat, valleys of the southern coast, Ybarbo found himself once again in mountain-like combat reminiscent of Italy. The Vosges was full of steep, rugged, thickly-covered hills full of trees and foliage. German troops began digging into the terrain, taking advantage of every piece of elevated real estate to try and hold off the GIs. 3rd Battalion began a week-long offensive fighting through several valleys, hillsides, and roadblocks as the men made their way towards the town of Tendon. Ybarbo, however, was forced to leave the company mid-attack yet again. On September 28, he was sent back to the 93rd Evacuation Hospital for a bout of malaria, which he had initially contracted back in North Africa. He was not discharged until October 12, and returned to K Company on October 16.

By the time Ybarbo rejoined the company the frontlines had mostly settled. The 36th Division was holding a long line through the forests going up towards the city of Bruyeres. His battalion of the 142nd Infantry was holding the southernmost part of the division line, its extreme right flank. The battalion was positioned along an extended series of hills stretching between the towns of Rehaupal and Le Tholy, both small, typical settlements of the Vosges filling small valleys between the tree-covered hills. The German forces opposing the battalion were the 716th Volksgrenadier Division and the 360th Cossack Regiment. The 716th was a veteran unit in name, having defended Omaha Beach during Operation Overlord. After suffering great casualties during that campaign, however, it was rebuilt with replacements before traveling down to the Vosges. The 360th was a unit of Russians conscripted into the German army, some voluntarily, some not. They were seasoned fighters of the Eastern Front, now facing off against the veteran T-Patchers of Italy.

Men of 3rd Battalion, 142nd Infantry Regiment in the Vosges.

36th Division troops on the move in France

Men of 3rd Battalion, 142nd Infantry Regiment in the Vosges.

The battalion had been settled into this line for a week before Ybarbo rejoined, giving them time to make defined positions and fortified foxholes using rocks, downed trees, and whatever else they could to provide extra cover from ever-dangerous artillery which liked to burst at the forest canopy and rain shrapnel down upon the men. The weather was also rapidly deteriorating, as cold and rain turned the hills into muddy sludge. This prevented armor from providing meaningful support for either side, with the hilly terrain relegated them to acting as mobile cannons for direct fire support. German forces deployed a number of self-propelled guns in the area which also liked to plague the T-Patchers located along the hillsides.

Combat in this area was like that faced by Ybarbo in Italy: endless patrols and artillery. Each night, the companies got men together for either recon or combat patrols. Recon patrols were mostly smaller groups sent out to determine enemy positions or strength, whereas combat patrols could vary in size from a squad to an entire platoon sent out to press an enemy position in force. Both sides traded these patrols nightly, probing each other in hopes of finding some sort of weakness.

Through these patrols, 3rd Battalion was able to find minefields, enemy movements, and scattered houses throughout the area being used as enemy strongpoints. A few homes dotted the hills around Rehaupal, leading both sides to fight for and defend them fiercely. While this was a fairly routine environment for someone like Ybarbo, the patrols provided invaluable experience for the many new men of K Company who had recently joined or only experienced the quick drive of Operation Dragoon, a wholly different type of fighting compared to what the vets of the company saw in Italy. Artillery was the other constant along this line, with both American and German forces trading many shells daily. One K Company veteran, Morris Courington, recalled the Vosges as the only time when it felt that German artillery was as equally deadly and numerous as their own.

The day after Ybarbo returned, K Company relieved I Company on a hillside directly butting up to the village of Rehaupal. The hill was forested but with some open fields overlooking the town. Several major German outposts towards the bottom of the hill kept the 3rd Battalion from entering the town freely, including some occupied houses, a fortified mill, and scattered German foxholes. K Company began securing their new positions by putting up rolls of concertina and barbed wire as well as sending out several raiding parties and combat patrols, which encountered many German machine gun and infantry positions. The Germans greeted their appearance with regular mortar fire.

Rehaupal, from the perspective of a K Company soldier on Ybarbo's Silver Star patrol in 1944. The buildings at the bottom of the hill are the old mill, which was occupied by Germans at the time. Immediately to the right of this photo would be the location of the house Ybarbo burned down.

An old foxhole from one of K Company's positions near Rehaupal.

View across the valley south of Rehaupal. German soldiers would have been occupying the opposite hill.

Rehaupal, from the perspective of a K Company soldier on Ybarbo's Silver Star patrol in 1944. The buildings at the bottom of the hill are the old mill, which was occupied by Germans at the time. Immediately to the right of this photo would be the location of the house Ybarbo burned down.

On October 21, Ybarbo performed yet another incredible act of heroism while taking his squad on a combat patrol going towards Rehaupal. The patrol, with men of his squad and others from L Company, set out at 0530 to test German positions at the bottom of the hill. At some point early in the patrol, Ybarbo took two of his men to sneak into Rehaupal in order to discover enemy troops positions there. They took note of their findings and began making their way back towards the rest of the patrol. On the way, Ybarbo spotted a house in a treeline a few hundred feet from the mill which several prior patrols had tried but failed to capture. It was surrounded by barbed wire and, according to prior reports, had a dugout just to its northeast with additional German troops. Deciding to take advantage of the opportunity, he ordered his soldiers to wait behind and cover him as he approached the position.

Sneaking in the early morning darkness, he was working his way, yard by yard, to the structure when out of nowhere a machine gun opened up from a window of the house. Dozens of bullets sprayed around Ybarbo, sending dirt flying into the air as he began an immediate dash towards the building, dancing around the fire. He was upon the house in seconds and, without thinking, chucked a grenade through an opening. The blast silenced the machine gun and the German manning it. Other Germans inside were stunned by this sudden assault and rushed their rifles through slits cut into the walls of the house to return fire. Ybarbo’s men continued pouring fire into the house as the rest of their patrol and German soldiers from the nearby dugout joined in. A full-scale firefight had begun.

In the chaos, Ybarbo, either through more explosives or some other quick-thinking action, managed to set the house on fire. With the position totally compromised, he ran back to his troops and led them as they slowly made their way back around the compound with the rest of the patrol and towards their company lines. As they made their withdrawal, they watched as the house became engulfed in flames, ammunition stored inside sending large blasts echoing through the valley. At least four German soldiers, burned to death, were seen being dragged out of the fire by enemy medics.

Ybarbo and the patrol finally returned to 3rd Battalion lines in the afternoon and were celebrated as a great success. Despite suffering five men wounded, it had neutralized a major German strongpoint and dealt a blow to the nearby enemy line. Later, Ybarbo was awarded a second Silver Star Medal for his actions near Rehaupal. The citation reads:

John Ybarbo, 38026352, Staff Sergeant, Company K, 142nd Infantry Regiment, for gallantry in action on 29 October 1944 in France. Sergeant Ybarbo was assigned the mission of leading two men from his squad on a reconnaissance patrol to locate enemy positions in a nearby town. After reconnoitering the village, he started to return to his unit with a report on the situation. While moving back to friendly lines, he passed a building housing an enemy strong point which several previous patrols had failed to neutralize. Sergeant Ybarbo instructed his men to wait for him at a safe distance from the house while he approached the hostile positions alone. As he neared the house, a machine gun opened fire, spattering dirt around him. Moving swiftly in the face of the hostile fire, he hurled a hand grenade into the emplacement, knocking out the enemy weapon. He charged the house and, while the hostile soldiers were still stunned by his daring action, set it afire, then returned to his company. The house was completely gutted by the fire, large stores of ammunition were exploded, many weapons were destroyed, and four enemy soldiers were burned to death. Entered the service from Victoria, Texas.

Note that regimental records describe this patrol as actually happening on October 21, 1944.

A map showing Ybarbo's actions near Rehaupal.

An entry from the regimental journal detailing Ybarbo's actions.

A March 1945 edition of the division newspaper announcing Ybarbo's second Silver Star award.

A map showing Ybarbo's actions near Rehaupal.

Over the next week, combat between K Company and the German defenders continued in a similar fashion. Patrols back and forth with artillery in between. No meaningful gains in terrain were made. On October 29, Ybarbo left K Company once again when a recurrent bout of malaria, first picked up while overseas in 1943, left him bedridden. He did not rejoin the company until November 11. At this time, the entire division had shifted forward several miles and the 3rd Battalion was resting in a reserve position near the town of Corcieux, located in a large open valley surrounded by the Vosges hills.

On November 14, 3rd Battalion took over for 1st Battalion in holding the division’s frontline near Corcieux, with each company responsible for a loose area surrounding it, as it was the dominant town in the valley. Ybarbo and K Company were moved to the village of La Houssiere, on the left flank of the battalion line. Over the next five days, most action occurred to the south in the I and L Company sectors. K Company, however, did send out numerous patrols around the northern edge of Corcieux, engaging in a few scattered firefights as the battalion slowly garnered the strength of German troops in the area. On November 19, after watching distant fires set by German troops to raze Corcieux, the battalion was finally able to enter the town to find it all but ashes with no Germans in sight.

Four days later, 3rd Battalion took part in the division-wide push towards Saint Die once it became clear that the Germans were falling back towards the Alsatian Plain. While the other regiments began engaging the enemy southeast of that city, 3rd Battalion took a convoy of trucks all the way to the town of Mandray, where they ended up having to wait overnight due to an ongoing firefight blocking their path down the road in the village of Le Chipal.

The Corcieux valley. K Company would have been at the bottom of the hill on the left.

The church in Corcieux, one of the only structures to survive the fires set by Germans.

The Corcieux valley. K Company would have been at the bottom of the hill on the left.

The battalion’s next target once again allowed Ybarbo to showcase his bravery, remarkably earning a third Silver Star Medal.

The convoy headed just to the north, through Basse Mandray and Wisembach, where the battalion dismounted and split into two groups. The target was the town of St. Marie-aux-Mines, an old mining town nestled into a deep valley surrounded by high rugged hills. The town marked the entrance of a long valley which spilled out into Alsace, the division's ultimate objective. The only way into the town, however, was a thin road traveling up a mountain pass which was suspected to host a German roadblock. To counteract this suspicion, two companies, I and K, were selected to flank the entire city by hiking across the mountainous hills to attack it from the rear. L Company, with some armor support, would take on the suspected roadblock as a distraction.

Ybarbo set out at 0530 with the I/K Company task force. Led by the battalion commander, the force marched through overgrown forests, up steep hills, and in total silence. Surprise was of the essence. Meanwhile, the distant sounds of combat echoed as L Company proved correct the presumptions of a roadblock on the mountain pass.

After several hours of marching, around 1320, the flanking force reached the edge of a treeline at the bottom of the large hill dominating the town. In front of them was a quiet and rather quaint St. Marie-aux-Mines. With L Company still duking it out at the now-distant roadblock, the two companies wasted no time in starting their attack. Ybarbo and K Company made their way down through a railyard while I Company mirrored on their flank. What they discovered, however, was a town of complacent and completely surprised Germans. As the T-Patchers began clearing the streets, Germans were caught eating breakfast, casually ride bicycles, and lounging about as if the war was many miles away. The surprise maneuver had worked, and dozens of Germans were rounded up in a matter of minutes.

Once the enemy became aware of the ruse, the day turned into bitter street fighting as the GIs worked building to building, street to street, rooting out individual and clustered groups of Germans resisting surrender. Around 1745, as the sun was setting, L Company radioed that it had finally broken the roadblock and was mopping up with twenty-eight POWs to its name. I and K Company had captured nearly a hundred at this point.

When word came of the roadblock’s defeat, Ybarbo was given a special task. While I and K Company were still locking down the city center, Ybarbo's 2nd Platoon was to hold an intersection at the edge of town where the road began winding up the hills towards the German roadblock. Their orders were to put a squad in each of the four concrete buildings dominating the intersection to capture or kill all enemy troops that might try to pass through, whether they were coming down from the roadblock or retreating from the city in that direction.

The intersection sat on St. Marie-aux-Mine’s western edge. Two of the buildings, on the southern side of the street, were part of a large factory complex. Across from them were two residential townhouses. After the platoon leader, Lieutenant Arthur M. Lane, put the squads in place, Ybarbo took charge of his men while Lt. Lane took up alongside them.

I or K Company troops in St. Marie-aux-Mines

The same church, today.

The flanking mission into St. Marie-aux-Mines

I or K Company troops in St. Marie-aux-Mines

Darkness blanketed the town while the bright glow of a full moon cascaded onto the cobblestone streets of the intersection. While they were resting in place, Ybarbo and Lane suddenly heard the distant clack of German jackboots on the road in the direction of the mountain roadblock. They were not sure how many of the soldiers were heading their way, but it was definitely at least several squads in size. While Lt. Lane was formulating a plan, Ybarbo looked up and told him he had an idea. When Lt. Lane asked what it was, all Ybarbo said was “I’ll show you.”

Ybarbo took off his steel pot and laid it on the floor, slinging his Thompson submachine gun across his shoulder as he walked out into the street all alone. The rest of the platoon looked through oepnings in their respective structures, watching as Ybarbo strolled casually down the right side of the street with his Thompson bumping behind his right hip. Before long, two lines of German infantrymen appeared marching down both sides the street directly towards the intersection. Lt. Lane and the rest of the platoon stared in silence as the Germans marched steadfastly towards Ybarbo with machine guns, MP 40s, and rifles in tow. They were not expecting Americans to be in the town and somehow did not notice Ybarbo as he moved through the shadows of the townhouses.

Lt. Lane described Ybarbo’s shocking actions in detail:

We could see and hear what was taking place through the windows and doors of the house we occupied. Ybarbo walked along the side of the road with a Thompson submachine gun behind his right hip–just strolling along naturally–directly towards two rows of enemy troops on both sides of the road.

Sergeant Ybarbo walked to within ten feet of the lead Germans, took two steps to the middle of the road, swung his tommy gun to hip level, and yelled as loud as he could, “Halt!”

The Germans looked at him and we could see their faces. Their jaws dropped and, without saying a word, they unslung their rifles, dropped them in the road, and held their hands up. I told two men to remain and cover us as I led other members of Ybarbo’s squad to support him. We ran down the sides of the road, past Ybarbo, pointing our weapons at the stunned troops and commanded them to throw their rifles and grenades on the road. They did, and just like so many dominos, [they all] surrendered!

Ybarbo captured at least twenty-one German soldiers without firing a shot. They were the LMG Platoon, 5th Kompanie, 454th Ostreiter Battalion, and had only began their combat career two weeks earlier. Immediately before Ybarbo’s daring capture, they had been defending the roadblock attacked by L Company. They were mostly conscripted Russians and Eastern Europeans sent by the German Army to the Vosges to build, and defend if needed, fortifications in the hills. The group Ybarbo captured managed to leave the roadblock shortly before it was overrun by L Company. They had no idea that both the roadblock and city had fallen during their march.

A map showing Ybarbo's capture of the German platoon.

The location of Ybarbo's actions. The building to the left is the old factory. He walked along the right side of the street to use shadows cast by the moon.

A description of the men captured by Ybarbo.

A map showing Ybarbo's capture of the German platoon.

The prisoners were added to the battalion’s pool, now totaling over 130 for the day. Lt. Lane later described Ybarbo as “the bravest soldier I ever met,” explaining that he always intended to put Ybarbo in for the Congressional Medal of Honor as “his actions were certainly above and beyond the call of duty and must have shortened the war.” While Ybarbo never received that medal, his actions at St. Marie-aux-Mines did earn him the Presidential Unit Citation and a third Silver Star Medal:

John Ybarbo, 38026352, Staff Sergeant, Company K, 142d Infantry Regiment, for gallantry in action on 25 November 1944 in France. After a successful surprise attack against a strategically important town, the 2d Platoon of Company K established a road block to stop expected enemy counterattacks. Sergeant Ybarbo, a squad leader in the platoon, heard a large group of hostile soldiers approaching the road block. He seized his light machine gun and fearlessly moved up the side of the street alone, silhouetted by the bright moonlight, to meet the enemy troops. Aware that the slightest misstep might mean instant death, he advanced cautiously, in the shadow of buildings, to a point within ten feet of the hostile force. He suddenly raised his gun and ran in front of the startled enemy soldiers, commanding them to surrender. Completely surprised by his daring trick, they immediately dropped their weapons. Sergeant Ybarbo captured 21 prisoners, two machine guns, four machine pistols, and fifteen rifles. His quick-thinking and aggressiveness prevented the enemy from reporting the location of his platoon’s road block. Entered the service from Victoria, Texas.

Ybarbo’s common expression of uncommon heroism made him one of only twenty-three men in the entire 36th Division with the distinction of receiving three Silver Star Medals, the nation’s third highest medal for valor.

Despite the smashing success of 3rd Battalion’s efforts to capture St. Marie-aux-Mines, they were ordered to keep up the pressure. As the element of the division closest to Alsace, it was ordered to leave the town and begin making its way through the forests to the south. While other elements of the division fought up the main valley road leading out of St. Marie-aux-Mines, 3rd Battalion marched around the Germans occupying the valley and towards the large hills overlooking Alsace.

German prisoners taken by the 142nd Infantry in another French town. Probably a similar sight to what Ybarbo marched back to the regimental POW cage.

Lt. Arthur Lane describing Ybarbo's actions in 1999. He misremembers a few things, such as a vast exaggeration of how many men were captured.

A member of L Company with a Russian Maxim machine gun being used at the roadblock into St. Marie-aux-Mines, demonstrating the Russian origin of the 454th Ostreiter.

German prisoners taken by the 142nd Infantry in another French town. Probably a similar sight to what Ybarbo marched back to the regimental POW cage.

Around 1715 on November 28, the battalion stopped at a small tavern nestled in an opening below their immediate target: the medieval fortress of Chateau du Haut Koenigsburg. At this point they had well surpassed the lines of German resistance in the valley of St. Marie-aux-Mines and had reached the twelfth-century castle which stood atop a steep hill nearly 2,500 feet above the Alsatian Plain, commanding views of the entire valley below. The French locals in the tavern warned the T-Patchers that the castle was well-armed and heavily defended. The regimental commander decided that the battalion would make its attack after dark in hopes of surprising the Germans inside.

The attack began around 1900 and by 1930, the castle belonged to the battalion. They were shocked to find that only hours before the German troops manning the fortress had left, heading down towards the rest of their forces in Alsace. Three prisoners were taken who had been left behind.

Throughout the next day the battalion primarily worked around the castle. Patrols were sent out to investigate areas of potential enemy strength while artillery observers atop the battlements helped the division commanders gain a critical strategic advantage. Able to observe the movements of all enemy forces in the plain, they soon found exactly where the Germans were and how they were deploying their forces to stop the now-inevitable breakout of the division into Alsace.

On November 30, 3rd Battalion was ordered down from the castle into positions along the smaller hills immediately bordering Alsace. K Company reached its hill, overlooking the village of Chatenois, in the early afternoon and began digging in. Observers from the company watched for German troop movements below and out onto the plain while most of the men sat and waited for orders to advance. Around 1800, a German patrol hit K Company but was quickly neutralized, ensuring its location was not revealed.

The morning of December 1, 1944, saw 3rd Battalion officially leave the Vosges and enter into Alsace. As a supporting battalion of the 143rd Infantry approached Chatenois from the north, K and I Company were tasked with entering the town from their high ground to the west. By 0750, it was theirs with little resistance.

Chateau du Haut Koenigsbourg during the war.

Chateau du Haut Koenigsbourg today, and its impresive view over the Alsatian plain.

The tavern where 3rd Battalion was warned about the German soldiers in the castle.

Chateau du Haut Koenigsbourg during the war.

3rd Battalion of ther 142nd, alongside 2nd Battalion of the 143rd, was then tasked with a new major objective: taking the city of Selestat. A major German supply hub in Alsace connecting German forces to the north and south, Selestat was now the target of a joint assault by those two battalions of the 36th Division and two more of the 103rd Division, which would pincer from the north. K Company began the operation by sending out patrols from Chatenois, but German artillery and roadblocks quickly sent the entire 3rd Battalion southward into the village of Kintzheim. Rather than attack Selestat directly from the west out of Chatenois, 3rd Battalion began cutting across vast farm fields to reach a small farm south of Selestat from which they would stage their part of the assault. Although some light German resistance was encountered along the way, they managed to reach the farm, known as Neubruch, and dug in for the night.

The early morning pre-light brought German artillery into their lines, hitting some men in I Company. Prisoners taken upon their arrival to the farm informed the battalion that the Germans had a large roadblock up ahead with an 88’ anti-tank gun and machine guns. The timetable for the attack left no flexibility for maneuvering, so it was 3rd Battalion’s job to power through and make their way into the city.

In front of the battalion was a narrow strip of ground to advance. The main road leading into Selestat was slightly raised above the surrounding fields, but on the right side, the terrain was boxed in by the Ill River. The Ill had also been intentionally dammed and flooded by the Germans, leaving the fields to the right of the road, which provided the best cover and route into the city, flooded. The decision was made to let I Company take the path alongside the road, leading an initial assault with several tanks and tank destroyers using the road itself.

Around 1150, after I Company had mostly broken up the roadblock, the full advance on Selestat began. I Company began working up the main road into a residential area while Ybarbo and K Company followed a stream on their right flank into some fields bordering the city, which were rather swampy due to the flooding. Throughout the day K Company, with two M-10 tank destroyers in support, tried working their way through the fields towards Selestat’s city center. Machine gun, artillery, and small arm fire, along with several STuG assault guns positioned across the Ill River, made it a difficult and slow fight across what was only a few hundred yards of ground. By 1530, K Company had made it into the houses at the edge of the city center. German infantry fought fiercely from street to street and the company was ultimately held up from its main objective, the main bridge heading into town, by a Panther sitting right next to it.

K Company continued its assault over the next two days. German troops and self-propelled guns still put up an intense fight and although the city was mostly secured by December 4, scattered pockets of resistance required mopping up as the rest of the division was solidifying the line to the south. On the night of December 5, 3rd Battalion was relieved from Selestat and sent to an area near the village of St. Hippolyte in reserve.

36th Division men outside of Selestat

The advance of the 36th into Selestat.

Damaged buildings in Selestat

36th Division men outside of Selestat

A welcome relief to the hard-fighting men of 3rd Battalion who had been in constant action for nearly a week and a half, the reserve designation also granted Ybarbo an unexpected surprise. On December 8, he and another staff sergeant in the company were told they had been selected for a special leave back home. Wick Fowler, a Dallas News war correspondent with the 36th Division, later wrote that around forty highly decorated and long-serving veterans of the 36th Division were selected for a thirty-day leave back in the United States. Ybarbo was sent to the 10th Replacement Depot for the journey, leaving Europe on December 22, 1944, for the United States.

Ybarbo arrived in New England around a little over a week later, spending the first month of 1945 visiting his wife, Wilma, and his young son, Jimmy, in Massachusetts. It was certainly a sweet reunion and a welcome break for the battle-hardened Ybarbo who had distinguished himself in combat on numerous occasions. Like any leave, however, it did have to come to an end. In early February he had to once again report to the Army for the trip back overseas. Although the exact time that he made it to Europe is uncertain, he likely arrived towards the end of February when the 36th Division relieved the 101st Airborne in the town of Haguenau.

Ybarbo’s return to K Company was a rather quiet one, as the company was neatly settled into defensive positions along the Moder River west of Haguenau. On the opposite side of the river, troops of the 47th Volksgrenadier Division built a mirroring defensive line along the edge of a large forest. Similar to earlier operations in the Vosges, the next three weeks were full of patrols across the icy river and into the German lines. At times these were simply recon missions. Other times, they sought to capture prisoners and gather intelligence on German strength in the area. The patrols were constant and not without hazard, but to a veteran like Ybarbo, it was just another day on the front.

On March 15, 1945, the entire U.S. 7th Army launched an assault against German troops up and down the line. For the 36th Division, this meant a full-scale attack across the Moder with the goal of pushing the Germans out from Haguenau and back to the Siegfried line several miles away. 3rd Battalion’s assault began around 0130 and by 0300, an intense firefight had broken out between the Germans and the GIs of I and L Company. K Company had not yet crossed the river when German artillery, responding to the threat, began bombarding the Moder and knocked out all the temporary bridges put up by the battalion. Rather than let the attack stall, K Company made a quick march to the town of Uberach where the 143rd Infantry had successfully kept the bridges intact. Ybarbo and K Company crossed the bridges and quickly advanced through the thick forests to join the rest of the battalion for the capture of Mertzwiller.

After a few days of fighting around Mertzwiller, the battalion mounted up on trucks for a two-day motor march all the way to Schweigen, just across the German border on the northernmost plain of Alsace. The massive combined operation left the Germans scrambling to the Siegfried Line as the 36th chased them back. On March 20, 3rd Battalion took part in the division’s assault on the Siegfried Line by moving west of Schweigen into the large and imposing hills that made up the edge of the northern Vosges. For three days the battalion battled it out with German defenders sitting in concrete bunkers atop a series of what can be best described as small mountains. These defenses, dominated by the “Grassberg Height,” were one of the battalion’s most formidable obstacles as they climbed near forty-five degree slopes in full combat gear while under fire in order to advance. On March 22, however, they managed to flank the hills and, after a prolonged firefight, forced the German survivors to surrender.

36th Division men undertaking a patrol across the Moder.

The crossing site of the 3rd Battalion across the Moder River

142nd troops on the move into Germany.

36th Division men undertaking a patrol across the Moder.

This was the last major combat Ybarbo experienced. As soon as the 36th Division secured the Siegfried Line, all of its troops, the 142nd Infantry Regiment included, made quick time racing to the Rhine River where they were ordered to hold for further orders. Rather than continue on pressing further into Germany, the entire division was assigned to perform military governance duties. From the end of March to late April, Ybarbo and his company were put into a small German village where they performed police functions, oversaw German prisoners, confiscated enemy weapons and equipment, and generally maintained order in the newly captured areas of Germany. It was quite a change of pace, especially being amongst a people whom they had been at war with for over three years.

At the end of April, 3rd Battalion went on the move once again, traveling deep into Bavaria as the 7th Army squeezed German forces desperately running towards the Austrian Alps. One of the last, but most memorable, sights that Ybarbo likely saw was the liberation of Kaufering IV, a subcamp of the Dachau Concentration Camp. The 36th Division came across the camp at the end of April and photo records show that 3rd Battalion did have some troops present during their time around the camp. Even if Ybarbo did not visit the camp, or any of its neighboring satellites, word spread quickly through the division of the horrors that T-Patchers had witnessed there.

As the war entered its final week, 3rd Battalion found itself at the base of the Bavarian Alps, facing numerous roadblocks which only slowed their advance. On May 6, 1945, while the battalion moved through the town of Fugen, word came down to hold fire as the entirety of German forces in the area were about to surrender. On May 8, 1945, the war in Europe came to a close.

Ybarbo, with three Silver Star Medals and multiple wounds to his name, was one of the first T-Patchers to be sent home. A “high-point” man who had made quite a name for himself in combat, he formally left the 36th Division, with whom he had served for over four years, on May 13, 1945. After traveling through several depots flush with men trying to return home, he arrived in Boston on June 15 aboard the Theodoric Bland, receiving his formal discharge from the U.S. Army a week later.

Ybarbo's award of the Croix de Guerre.

A Texas newspaper discussing Ybarbo's return home in 1945.

3rd Battalion men traveling into Germany.

Ybarbo's award of the Croix de Guerre.

With such an abrupt change from his last four years as a soldier, Ybarbo struggled returning to life as a civilian. Through the summer and fall of 1945, he sought to find a long-term civilian job but simply could not settle into the routine. On October 21, 1945, the French 1st Army awarded him the Croix de Guerre with Gold Star, for “exceptional war service rendered in the course of operations to free France." Likely reigniting his wartime memories and feelings, he began contemplating a permanent return to the Army. On February 7, 1946, he made the choice to re-enlist.

As an experienced non-commissioned officer, Ybarbo was quickly sent overseas for duty in the occupation of Germany. Leaving behind his wife and young son, he joined the 3rd Infantry Division as a military policeman. He traveled around the American occupation zone in this capacity until late 1946 when the 3rd Division returned to the United States. Ybarbo’s enlistment was not up, however, so he transferred into HQ and Service Troop of the 14th Constabulary Regiment, a specialized policing force responsible for manning positions along a 200-mile border with the Soviet occupation zone. This also meant he served more specialized policing functions, assisting local police with raids, arrests, investigations, and other general law enforcement for the turbulent postwar German population.

Ybarbo’s wife, Wilma, and his son, Jimmy, joined him in Europe in December 1946. They were given a billet in the town of Fritzlar, Germany, and could finally begin a meaningful life together as a family, uninterrupted by his military service. Unfortunately, the Ybarbo Wilma met in Germany was not the same she had known for many years. Over the next many months, she noticed a change in his behavior. He became less responsible, staying out late and drinking often with buddies. His drinking got so bad that she later recalled “he could carry no more in his currency book than he earned each month,” spending all his spare income on alcohol or hosting parties for people. He also began exhibiting depression, high anxiety, a furious temper, and bouts of extreme anger when aggravated. On several occasions he accused Wilma of being unfaithful and cheating on him with other soldiers. While there was never any formal diagnosis of service-induced post-traumatic stress disorder, it is not hard to imagine that the horrible things Ybarbo had witnessed and done during the war were finally taking their toll.

On August 30, 1947, Ybarbo and his wife attended a friend’s wedding, who Ybarbo had accused Wilma of cheating on him with. At one point, their son, Jimmy, saw the groom and began crying saying “come back to mommy.” Ybarbo was absolutely livid and that night beat Wilma in a rage. Several months later, in November, the couple’s housemaid, Anne-Marie, was cleaning the house while the couple sat in the living room. Ybarbo randomly announced that his father was dead and when Wilma replied “Why, no, your father isn’t dead, John,” Ybarbo began to beat her severely. He then shouted to Anne-Marie to get him a pistol, which had been given to him by the local PX manager illegally, so that he could shoot everyone. Instead, she hid the pistol. Ybarbo began searching for the weapon and after several days of not finding it, his mood calmed.

Ybarbo with the 3rd Division in Germany

Wilma, on left, with Jimmy, on right.

Ybarbo with the 3rd Division in Germany

These were just two recorded instances that demonstrated a steep decline in Ybarbo’s marriage. Wilma soon began to suspect that Ybarbo was actively sleeping with several German women, including a girl named Margaret.

One night, after their son had gone through an operation, Ybarbo once again came home late and refused to explain where he had been. Wilma went to bed and began reading, trying to go to sleep, when John burst into the bedroom angry. He accused her of not being a good wife, to which she retorted that she knew about his affair with Margaret. Ybarbo fumed, admitting to Wilma that he had fathered a child with Margaret while Wilma was in the United States. He had refused to support the child, leading her to give the baby up to an orphanage. The two argued until they fell asleep. Around 0600 the next morning, he ordered her to make breakfast to which she refused, so he angrily stormed out. At 1030, he returned home with a man for a few drinks and after demanding for Wilma to make them lunch, they got into another “vicious” fight.

This long period of marital discord reached a tragic climax on September 20, 1948. Throughout that September, Wilma barely saw her husband. He was constantly absent until late at night, always out with buddies or volunteering for their turns on duty. On the evening of the twentieth, he brought to their billet several GIs and two German girls, including a former maid. He and Wilma then visited an NCO club for a few hours before the maid and one of the GIs brought them home. The events that then transpired are best left to trial testimony detailed below, but what is indisputable is that while the guests were in the living room, John and Wilma got into yet another argument. Just around midnight, several gunshots rang out and Ybarbo fell, grasping his gut on the bathroom floor. “She shot me,” he gurgled, as the other guests ran to the scene, finding Wilma with a Hungarian pistol in her hand.

Ybarbo was immediately rushed to a hospital nearby where he underwent emergency surgery and remained in critical condition. On October 20, 1944, the triple Silver Star recipient, who had survived countless harrowing battles in Italy, France, and Germany, succumbed to the wounds left by his own bride.

What came next is a gripping unknown story of legal and historical interest.

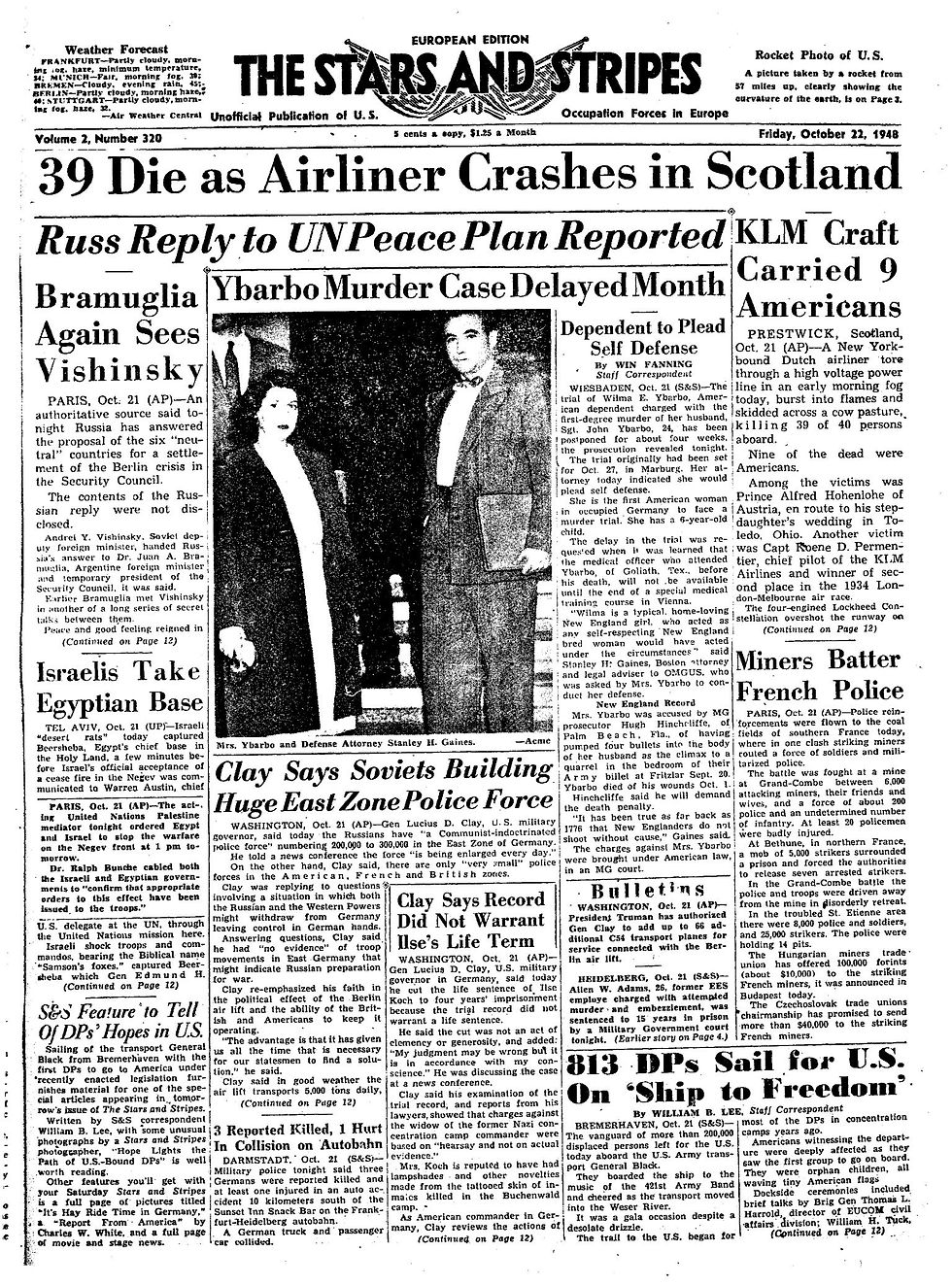

An article in Stars and Stripes describing Ybarbo's shooting.

An article in Stars and Stripes describing Ybarbo's shooting.

With the death of Ybarbo came a full investigation by the Constabulary. On October 20, 1948, the Military Government served Wilma an indictment charging her with first-degree murder under American military law. Her appointed defense attorney was Military Government attorney Stanley Gaines. Gaines was a fellow Massachusettsan, from Boston, serving as an advisor to the occupation military government. Wilma was originally given one week to prepare for trial, set to begin on October 27, but it was almost immediately postponed for four weeks as the medical officer attending to Ybarbo was in a training course in Vienna. She was confined to a local dependent community’s dispensary pending the trial. She was given a bedroom, office, and German maid to accommodate her unprecedented situation. The prosecutor assigned to the case was Hugh L. Hinchcliffe, a high-level member of the legal staff for the American military government.

The story made international headlines. Beyond the sensational tale of a war hero’s wife shooting him dead overseas, this was also the first time an American woman in occupied Germany was charged with murder. Gaines told the hounding press that she planned to plead self-defense and that she acted as “any self-respecting New England bred woman could have acted under the circumstances.” Wilma, although soft spoken, was not one to stay silent on the issue. In an October 22 interview with Stars and Stripes, she related how much she had loved her husband. “He was a fighting man and deserved the Congressional Medal of Honor if ever a man did.” The article detailed Ybarbo’s many decorations as well as her testimony that he had changed after the war. She told the public that it was “so useless to quarrel with him,” and that his decision to work nearly every day, including holidays, naturally led to strife.

Wilma awaited her trial for over two months as various interruptions caused delays. Her father even offered to fly to Germany and assist in whatever way he could, but Gaines did not think it was necessary for her defense. On December 1, Wilma was served with additional charges under the German Criminal Code. This caused Gaines to raise serious questions about the jurisdictional validity of the proceedings. Wilma was being charged and tried by the Military Government’s 3rd Judicial District Court for charges under both American military and German law. She was the first American dependent to be tried by an Military Government Court outside of the United States on a capital charge, and thus questions of the court’s authority to prosecute her, as an American citizen and civilian, as well as the type of law that applied, began permeating public debate in Germany and in the United States.

Wilma with her attorney, Stanley Gaines

Wilma on the front page of Stars and Stripes

A Stars and Stripes Article on the trial.

Wilma with her attorney, Stanley Gaines

On December 14, 1948, Wilma’s trial began in Marburg, Germany. The prosecution opened the day by arguing that this was premeditated murder, signaled strongly by the fact she fired four shots at Ybarbo. Wilma’s lawyers argued that this was clearly a case of self-defense and entered a formal plea of not guilty.

The rest of the day was filled with heavy philosophical and constitutional arguments regarding the jurisdiction of the Military Government (MG) Court. Her second-chair defense attorney, Robert Conner, argued that the court lacked jurisdiction as she was denied her constitutional right to a trial by jury. This was factually correct, as the MG Court did not permit a jury to be present. The entire case would be heard and decided by a three-judge panel of MG judges. Worth B. McCauley, the chief district attorney for the MG Courts, argued on behalf of the government, stating that the U.S. Constitution does not follow the Army and that dependents leave their constitutional protections behind when leaving the United States.

All three judges ruled against Wilma's jurisdictional protests. Judge DeWitt White gave the opinion at the end of the hearing that the MG Court did have jurisdiction despite no existing precedent supporting this finding. He ruled that under Article 2, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution, the President uses his war-making power as Commander in Chief to set up MG Courts. This meant that the MG Courts were neither Article I nor Article III courts (those set up by the Congress), and thus not subject to any constitutional protections understood to exist within courts originating from those articles. As a result, the MG Courts were like any other military tribunal and subject to their own sets of rules and protections, including the ability to remove the jury trial right. This was a major piece of legal precedent that set up a real constitutional question, and was speculated by many at the time to be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court should Wilma end up losing. The only witness heard on this day was Captain Frank M. Ritter, Ybarbo’s company commander in the 14th Constabulary, who testified on Ybarbo’s history and service.

The next day was full of critical witness testimony. First on the stand was Lieselotte Tessner, a twenty-seven year old German war widow serving as the Ybarbos’ maid who was present at the billet on the night of the shooting.

According to Tessner’s recollection, she arrived at the billet around 1830 with another German woman, Elfriede Krummelbein, and Jimmy, the Ybarbos’ son. Shortly after, two GIs of the constabulary, Corporal Morris J. Burr and Private First Class Paul K. Johnston, arrived and the Ybarbos left as a couple for the Fritzlar NCO club. Around 2230, a third GI, Corporal Lee V. Jacobs, reached the billet. Tessner and Jacobs took a truck to the NCO club and picked up the Ybarbos. When they arrived home, Wilma went back into the nursery while Ybarbo became angry that Cpl Burr and Ms. Krummelbein were still in his billet. He went back to the nursery to talk with Wilma and then returned to the kitchen.

Later in the evening, Tessner recalled standing in the nursery with Cpl Jacobs when Wilma called to her from the bedroom. Wilma was wearing a slip and bra, laying on one of the twin beds with their six-year-old son in the other. Tessner described how Ybarbo was standing there bleeding freely from the nose. “Look at my nose,” he told Tessner, “she hit me back!” Suddenly, Ybarbo attempted to swing at Wilma, causing Tessner to grab him around the waist before he stopped and left the room. Tessner then ran to a wardrobe to grab a pistol that she had seen stashed there a few weeks earlier. Seeing that blood had gotten onto Tessner’s clothes, Wilma told her to leave the gun alone and go and wash the blood off.

A map of the Ybarbo apartment on the night of the shooting.

A Stars and Stripes article on the trial.

A Stars and Stripes article on the trial.

A map of the Ybarbo apartment on the night of the shooting.

Tessner then testified on the killing. Around midnight, Tessner was in the nursery door when she saw Wilma dressed in a housecoat standing a few feet in front fo the bathroom, a pistol in her right hand. As Wilma raised the pistol and pointed it through the bathroom door, Tessner explained that “I cried out her name but she only motioned me with her left hand. She fired.” After the first shot, Tessner closed the nursery door and heard terrible moaning from Ybarbo coming from the bathroom. Ybarbo yelled “Jacobs, Jacobs, she shot me.” Tessner then remembered hearing two more shots ring out close together. She opened the door and saw Ybarbo on the floor in the hallway, just in front of the kitchen door with Wilma leaning over him.

Next on the stand was Major Robert G. Salasin, chief of surgery for the 388th Station Hospital in Giessen. Ybarbo had been admitted to his hospital after the shooting. He testified on the three-hour emergency operation he performed on Ybarbo for his abdominal wounds, and confirmed that he died from these wounds. He stated that Ybarbo had been shot three times: once in the abdomen, once in the right ankle, and once in the right arm near the elbow. This third shot had course down through his chest, however, entering his liver. Major Salasin remembered Wilma visiting Ybarbo in the hospital. She only ever asked three questions: How many times was he shot, how long was he going to be in the oxygen tent, and whether he would be able to go home.

The trial resumed on December 17 with the testimony of an Army criminal investigator. He confirmed that there was another pistol in the house in addition to the murder weapon. While in the billet, the investigator found a Czech pistol on top of a heap of lingerie, which was different from the .32 Hungarian pistol used to shoot Ybarbo. The bullet casings found at the scene had indeed matched the Hungarian pistol and one expended bullet was found under the floorboards where Ybarbo had fallen. He also stated that Wilma was very calm and collected throughout the investigation process, expressing no regret for her actions. She never appeared nervous and volunteered a long confession after everything happened. While letting her pack up clothing for her confinement, she confirmed that a stain in the middle of their bed was blood. Investigators had also learned that two days before the shooting, Wilma told their two maids that they “almost didn’t have a boss anymore,” but did not explain what exactly that meant or why she said it.

At this point, the defense was allowed to argue before the court to confirm a finding of premeditation and malice in her shooting. Her statements to the maids, combined with multiple fired rounds, they argued, showed she had complete intent to end his life before the events of September 20. Unlike U.S. civil courts, the MG Court issued a preliminary ruling finding that there was no premeditation. This preliminary decision, at the least, removed the possibility of Wilma receiving the death penalty.

On December 20, trial continued with what was probably the most dramatic testimony of the entire trial. Wilma took the stand, speaking in a low, clear voice, while wearing a formal but not flashy suit.

Four of the main witnesses in the Ybarbo trial. From left to right is Elfriede Krummelbein, PFC Paul Johnston, CPL Lee Jacobs, and Lieselotte Tessner.

Four of the main witnesses in the Ybarbo trial. From left to right is Elfriede Krummelbein, PFC Paul Johnston, CPL Lee Jacobs, and Lieselotte Tessner.

Wilma testified as follows.

The day after Wilma arrived in Germany on December 4, 1946, Ybarbo told her that he was going to be the father of two babies by young German girls. She claimed that from that day onward, Ybarbo beat her regularly. Before Ybarbo had come back to Germany, she claimed he was a “good man.” After returning to Europe, however, there was a “change” to him noticeable as soon as she saw him. She alleged that Ybarbo told her they would have to employ a German girl, Anne-Marie Nolte, as a maid since he had impregnated her and she needed support. Eventually, she had a miscarriage, but the damage to their marriage was done.

Wilma recalled the first major beating as occurring in June 1947 after which she sought help from an Army chaplain. Ybarbo promised her that he would not do it again. The second beating occurred on August 30, 1947, after the wedding reception mentioned above. She said each of these beatings were usually done by fists, open hands, and choking. She recalled Ybarbo once sending Anne-Marie, the maid, to get a pistol, but that Anne-Marie had hid it from him.

Viscous arguments were a regular occurrence for the couple. She related times when Ybarbocomplained about their marriage, telling her that they were “incompatible sexually” and accusing her of alienating their son. She retold how one time “he was going to kill himself, but said that before he did, he would get me first.” He then tightened his arm around her neck and allegedly said “[s]ee how easily I could kill you?" Just two days before she shot Ybarbo, they had a bad fight only because she wanted to leave a lamp on to read a book while Ybarbo wanted to sleep. He had also expressed serious sentiments of suicide, leading her to take the Hungarian pistol in their wardrobe and put it into her pocketbook, so that he would not know where to find it.

According to Wilma, his previous beatings and threats, causing her severe physical, emotional, and psychological harm, plus a threat to beat her again that night, is what led to the shooting on September 20, 1948. She “could no longer endure” his beatings and repeated threats that he would kill her.

On the night of the shooting, she remembered her husband announcing that their two visitors, Cpl Burr and Cpl Jacobs, and the two German maids, Ms. Tessner and Ms. Krummelbein needed to clear the house because he wanted to go to bed. Wilma objected and wanted them to stay. Ybarbo then “roughly bustled” her into the bedroom, slapped her, and pushed her on the bed. Wilma testified

Then, for the first time in my life, I struck him back. I hit him on the nose and made it bleed. John said he would go to the bathroom and wash the blood off, then would come back and black my eyes and break my nose and teeth.

When Ybarbo was in the bathroom, Wilma began thinking of all his previous threats. “I was afraid of what he would do to me,” she told the court. She proceeded to grab the pistol which she had taken months earlier and put into her pocketbook, put on her housedress, and followed Ybarbo down the hall to the bathroom. She continued, saying

When I opened the bathroom door, John was crouched over the bathtub. He sprang at me and I fired. He yelled that I had shot him and grappled with me for the gun. It went off twice more as we wrestled to the floor. He had threatened to kill me and I thought he would kill me.

As the two German women ran for help, Wilma described holding Ybarbo’s head and giving him some water from her hands while he lay on the floor. A neighbor came by and got him blankets as they awaited an ambulance. “I saw he wasn’t mad at me anymore,” she told the court softly.

At the end of Wilma’s testimony, the judges reaffirmed their decision that there was no premeditation under U.S. law and that the murder was not done in a “treacherous and cruel manner,” as was required under the relevant German law.

Wilma with her two attorneys in court. On the left is Robert Conner. Stanley Gaines stands on the right.

Wilma on trial with Mr. Gaines

Wilma's testimony as reported in Stars and Stripes.

Wilma with her two attorneys in court. On the left is Robert Conner. Stanley Gaines stands on the right.

On December 21, trial continued with final testimony from Anne-Marie Nolte and Corporal Burr. Ms. Nolte, a pretty blonde-haired blue-eyed twenty-three year old German girl, testified that she had indeed been intimate with Ybarbo before Wilma came to Germany. She confirmed that she had once been impregnated by Ybarbo before losing the child and was employed by them as a maid. She was in the house in August 1947 when she watched Ybarbo “thrash” Wilma with his fists, knocking her to the floor, splitting her lip, blacking her eyes and nose, and smashing her fingers. At this time, Ybarbo asked her to get a pistol but she ran to the kitchen and hid it. The beating continued inside the bedroom and she was afraid to stay inside the house.

Corporal Burr’s testimony was more limited. He described several times he had seen Wilma with a bruised face, in line with beatings, and confirmed that Ybarbo complained to him about a German girl he had impregnated pressuring him for money. He also gave a detailed account of a patrol with Ybarbo one time where Ybarbo accused him of sleeping with Wilma. After vigorously denying the allegation, Burr gave Ybarbo a pistol and said that he could shoot him if he really thought that. Ybarbo instead loaded the pistol and threatened to commit suicide. Burr wrestled the pistol from Ybarbo’s hands, but afterward watched as Ybarbo broke down.

The final day of trial was held on December 22. The prosecution gave their final argument, avidly pressing that she had shot Ybarbo with malicious and cruel intent by doing it three times. She did not need to use a gun, they suggested, as she could have had the others in the billet help restrain him. In their eyes, she was the aggressor for taking the pistol and following her husband to the bathroom where she could fire on him. Gaines argued on behalf of Wilma, citing over a dozen instances of U.S. case law suggesting this was a clear case of self-defense to save herself from continued physical and emotional abuse by her husband. At the very least, there was reasonable doubt warranting a not guilty verdict. She had suffered several severe beatings by her regularly drunk husband. This time, since she had struck him back, there was harsher anger and even more fear of severe retaliation. Gaines explained that military government ordinances advanced against Wilma, such as those prohibiting attacks on members of the armed forces, were not intended to ever apply to dependents like her. He ended his closing by posing the court to consider the simple question of “did Mrs. Ybarbo act in a reasonable manner?”

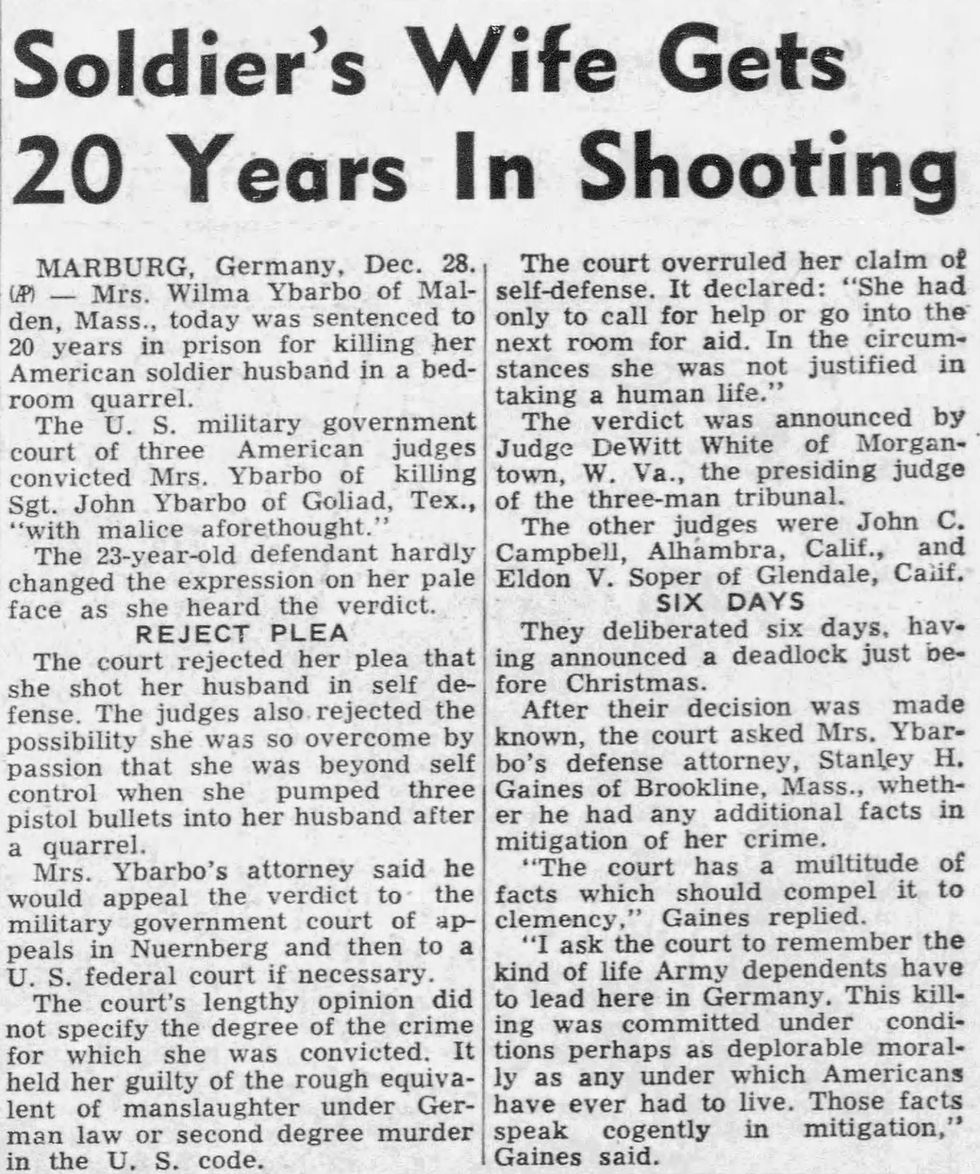

As the court recessed for Christmas, the verdict was not reached until December 29. The courtroom was crowded with reporters and locals as each side sat at their benches. The judges began by reading off a long list of factual findings based upon the evidence presented. According to the court, she did not have sufficient provocation to use the pistol four times to prevent another beating. They also suggested that this was not manslaughter, but murder, as it was done with malice aforethought. She was found guilty. Due to the circumstances, however, she was not sentenced to death. The court instead sentenced her to two dual twenty-year terms under both U.S. and German law which would be served simultaneously.

As the verdict was announced, Wilma’s lips trembled and tears filled her eyes. After a moment, however, she regained her composure and stiffened her lip while the sentence was read. After she was led away in handcuffs by members of the 532nd Military Police Company, Gaines told the reporters that they would be appealing the decision to the Military Government Court of Appeals in Nurnberg, and that this could potentially reach the Supreme Court of the United States. Wilma was taken into custody at the 25th General Dispensary in Bad Wildungen awaiting transport to serve her sentence in the United States.

When Wilma’s mother was told of the verdict, she collapsed. Ybarbo’s sister, all the way back in Texas, told local news that she was glad to hear the outcome and that she could never forgive her for what she did. Ybarbo’s blind and aged father, however, did feel sorry for Wilma, although he did not think she should have expected to go free after taking someone’s life.

Wilma learning her verdict.

A Texas article about her sentence.

Wilma learning her verdict.