_edited.png)

The 36th Division Archive

Private First Class Harvey Yates

C Company, 1st Battalion,

502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment,101st Airborne Division

Harvey Yates was born on July 7, 1924, in Washington County, Kentucky. He was the middle of nine children. The family operated a livestock farm throughout his childhood near the county seat of Springfield. It was a prosperous time in the region’s history, full of agricultural production, making the rather rural county quite lively as Yates grew up. As he was preparing to graduate high school, however, the family decided to leave their longtime home and move to Harrodsburg, in neighboring Mercer County, after purchasing a new and larger farm.

Yates decided to embark on his own journey. While his parents and younger siblings moved to Harrodsburg, he, at only eighteen, set out for the big city of Louisville alone to seek out new opportunities. He managed to set up in an apartment above some shops off West Broadway. Rather than pursue the agricultural life of his father, he took advantage of the growing city and found employment as a laborer with Ford, Bacon & Davis, a national construction firm. The firm was involved in numerous important projects around Louisville, keeping Yates busy as others his age began lining the street wearing olive drab uniforms. The United States was at war.

Yates' military artifacts.

Yates' dress uniform.

Miscellaneous patches, medals, and ribbons kept by Yates.

Yates' military artifacts.

Around this time, Yates, like many young men, fell for his lifelong love, Christine Lyons. Her family was also a Louisville transplant, from Union County, and her father worked as a carpenter alongside Yates. The two grew fond of each other but were not destined to pursue anything permanent quite yet. In March of 1943, Yates received his draft notice to enter the United States Army, officially enlisting on March 30. Saying goodbye to his loved ones in Harrodsburg and Louisville, he traveled to Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indiana to begin his military service.

After completing his basic training as an infantryman, Yates was assigned to HQ Company, 2nd Battalion, 262nd Infantry Regiment, 66th Infantry Division out of Camp Blanding, Florida. The 66th was a relatively new division composed of men from all around the country. Yates traveled with the division for the latter half of 1943 to Camp Joseph T. Robinson, Arkansas, and kept up his training as an infantryman.

In early 1944, however, Yates caught wind of a unique branch of the Army. It offered higher pay and service with “the best” the Army had to offer. It was the Airborne Infantry. Although it was an entirely voluntary branch, Yates figured he was up for the challenge. Once the orders came through granting his request, he formally left the 66th Infantry Division on March 1, 1944, and traveled to Fort Benning, Georgia, to begin training as a U.S. Army paratrooper.

He was assigned to L Company, 1st Parachute Training Regiment, and underwent the rigorous physical and mental conditioning required of the paratroops. This included long marches, intense obstacle courses, advanced rifle training, and, of course, five airborne jumps. Like many other paratroopers, it took Yates some experience to get the hang of them. On one particularly rough jump he suffered a bad landing, leaving him in a hospital for four days with a contusion and bad bruises on his heels. By May of 1944, he received his MOS as an ammo bearer for mortar crews and transferred to C Company, 2nd Parachute Training Regiment for additional training.

Towards the end of May, Yates graduated from Parachute School and received his jump wings. While he was on his end-of-training furlough, paratroopers made news nationwide as they jumped into Normandy behind enemy lines during the D-Day invasion. His new skills all but guaranteed that after his furlough, it was only a matter of time before he went overseas. His time came in July, traveling with a group of replacement paratroopers to England.

Jump training at Fort Benning

Jump training at Fort Benning

Jump training at Fort Benning

In early August, Yates received his combat assignment to the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division, filtering through its Service Company alongside many other replacements. The 502nd had just distinguished itself in the Normandy Campaign, but needed replacements like Yates to fill its ranks after the losses suffered during its bloody baptism of fire. On August 13, 1944, Yates was permanently assigned as an ammo bearer in HQ Company of the 1st Battalion, likely as a member of its 81mm Mortar Platoon. In this capacity, his role was to carry and supply ammo to the mortar teams to provide steady support to the infantry of the battalion. It was likely a somewhat awkward time, with new men like Yates trying to integrate into the well-established and now veteran companies of the 502nd. Nevertheless, he only had to wait a month before they were all once again tied together in combat during Operation Market Garden.

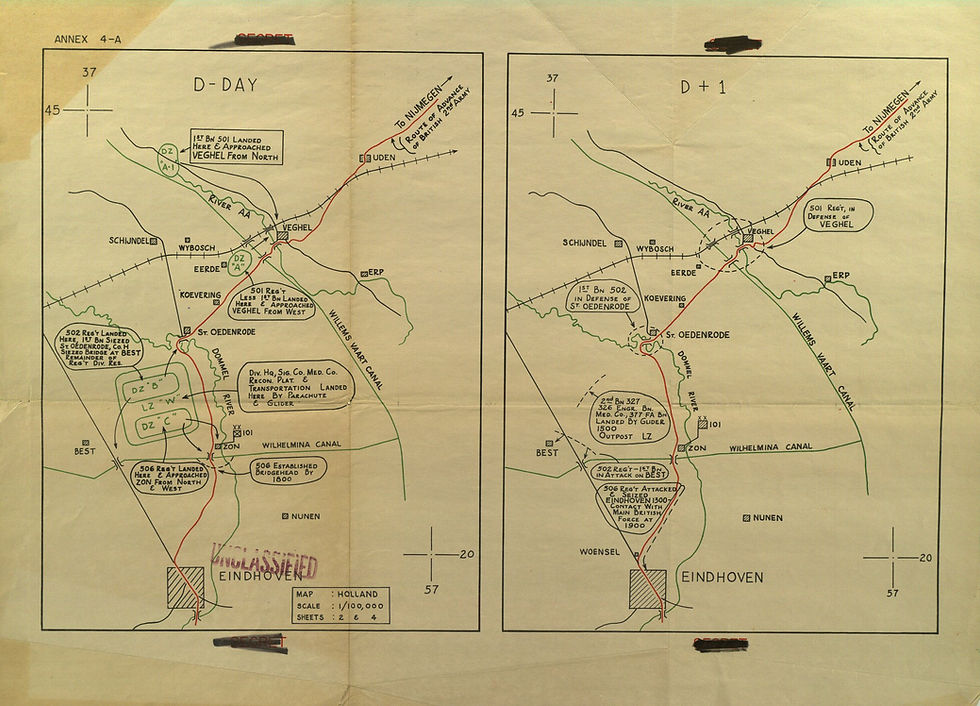

Market Garden was a planned joint airborne and ground assault into the Netherlands, requiring a series of airborne units to hold key highways and bridgeheads throughout the country in order to open a direct pathway for armor and ground troops into Northern Germany. The 101st Airborne was slated to land around a few key towns such as Veghel, St. Oedenrode, Son, and Eindhoven, to control and keep open one stretch of the highway.

Around 1030 on September 17, 1944, Yates and the rest of his company loaded aboard C-47 transport planes of the 438th Troop Carrier Group at Welford, England. 1st Battalion was designated to jump alongside the Division HQ jumping echelon along with some engineers and artillery. While flying over Holland, flak and small arms fire burst around them, wounding some troopers and knocking a few transports out of the sky. They were among the last parachute serials to drop, jumping at 1325 near Best. Yates finally entered combat.

The 1st Battalion of the 502nd had veered off of the plotted course to evade some floating stragglers of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, meaning Yates and the others landed in the southern edge of Drop Zone C. When the green light came on, Yates and the others leaped and steered towards the red smoke they thought signaled their targeted area. It was, in fact, the signal for 1st Battalion of the 506th. Despite the mishap, Yates landed safely and began traveling with the rest of the battalion to link up with the 502nd at Drop Zone B.

Jumping into Holland From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

Map of the dropzones and objectives of the 101st Airborne in Market Garden

Yates joining the 502nd on August 17, 1944.

Jumping into Holland From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

With the 506th heading to the south and the 501st to the north, the 502nd was tasked with holding the key middle ground of the division. Within an hour, the regiment was fully assembled and 1st Battalion headed off for its initial task: the capture of St. Oedenrode. It was an important town in the 101st Airborne sector which was necessary to the division’s grand objective of holding the main highway. It also contained two important highway bridges over the Dommel River. C Company led the battalion into the town, followed by Yates and the battalion headquarters. B Company flanked to the right.

P-51 fighters strafed German positions, tanks, and troops as the battalion approached the town, softening the enemy defenses. It did not take long for street fighting to break out across the city. B and C Company took the brunt of the action, while the mortars of Yates’ platoon provided supporting fire from the rear. The firefight did not last terribly long, however, and the town was captured with nearly eighty German casualties recorded.

1st Battalion immediately set to work making defensive positions all across the town and bridges. Word came in from members of the Dutch Underground that the Germans were regrouping to attack from Schijndel, about four miles down the main road. The old monastery in the town quickly transformed into a field hospital, and was right in the middle of much of the fighting. By the end of the day, St. Oedenrode was secure, with the Germans back across the Dommel River. The next day was spent shoring up the city’s defenses with sporadic small-unit action between the paratroopers and bands of German soldiers.

In the mid-morning of September 19, the sounds of British tanks filled the ears of the paratroopers. The first tanks arrived around 1000, rolling through the corridor over a bailey bridge at Son. Tanks, halftracks, trucks, laden with troops, chugged their way northward past the Americans. One British tank, however, struggled. A Sherman Firefly commanded by Sergeant James “Paddy” McCrory dropped from the column due to engine trouble, pulling into the streets of St. Oedenrode with 1st Battalion. The tank could only travel a mere five miles per hour, but was not ready to give up the fight. Instead, his crew volunteered to join several of the battalion’s battle patrols sent to push back German troops along the Schjindel Road. Throughout the day the combined force accounted for several German vehicles, flak wagons, an 88, an ammo truck, a number of enemy troops, and several defensive positions.

German prisoners taken by members of C/502 in St. Oedenrode. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

German prisoners taken by members of C/502 in St. Oedenrode. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

The following morning found 1st Battalion under a heavy artillery barrage, with four men killed near Yates at the battalion command post in the center of town. The Germans launched a counterattack in force towards St. Oedenrode, leading the paratroopers to ask McCrory to lead his tank into battle once more. Down a few crew, he recruited three of the troopers to join him in the tank and set off along the road to Schjindel, leading an attack which destroyed an 88, knocked out two 20mm flak guns, and stifled an enemy infantry attack. The German advance stalled, and the battalion once again managed to hold the town. McCrory was later awarded the Silver Star Medal, and his crewmen put in for the Legion of Merit.

1st Battalion continued to hold St. Oedenrode from repeated German attempts to move up the roads leading into the city. Two other British tanks joined their defense, but were knocked out by rockets, leaving only McCrory to continue his valiant support. On September 22, 1st Battalion tried to push up the roads, meeting a large contingent of German Fallschirmjager. Fighting was brutal between the trees, farms, dikes, and roadways, with tank duels taking place between German self-propelled guns and new British tanks. By the evening, the battalion was forced to fall back to St. Oedenrode. Yates’ mortar platoon played an important role in supporting these attacks, with Yates likely spending most of his time lugging the heavy shells back and forth to the front.

Until September 30, Yates and his battalion fought fiercely to defend St. Oedenrode and did their part keeping open the road to Arnhem, which had quickly earned the nickname “Hell’s Highway.”

On the last day of September, the men of 1st Battalion were relieved and climbed aboard a set of trucks on a side road off of the main highway. They began moving northward, passing burned out hulks of tanks and destroyed buildings, as they drove to the bridge at Veghel. There the men stopped, turned off, and set up a large bivouac in a field to rest, clean up, and filter in personnel changes. One of the internal transfers was Yates. Although he had done well serving in the battalion headquarters, he was transferred to C Company as a rifleman, taking on a more direct frontline role. Thankfully, he was able to enjoy a few days of rest, allowing some downtime to mesh with his new company-mates.

A British tank supporting troopers of the 101st Airborne. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

Map of St. Oedenrode. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

A British tank supporting troopers of the 101st Airborne. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

C Company was told to roll up their packs on October 3, following the battalion as it drove up to Nijmegen as a standing reserve for the 82nd Airborne. On the fourth, they moved again up the highway through Uden, detrucking at Groesbeck Heights, a wooded area of evergreens. It was here that the 1st Battalion began prepping to move onto “the Island.” The Island was a flat stretch of land well below sea level between the lower Rhine and Waal Rivers. By this point in Market Garden, however, it was clear that the campaign had failed to meet its primary objectives. The advance had stalled with the British failing to capture Arnhem, and now the 101st was slated to fill the line and hold off the Germans from making the situation even worse.

As Yates and the rest of C Company entered the line near Elst, they were forced to crawl up to the foxholes of British soldiers they were replacing in the early morning of October 5. German artillery across the Rhine had sighted in Allied positions all across the Island, with their new homes included. It was two men to a foxhole and, during daylight hours, neither could poke his head above the top of the hole. There was no way to move about in the day without drawing intense German sniper or artillery fire. With water regularly seeping into the bottom of their holes due to the low terrain, it was quite a dreary yet hazardous existence.

By October 10, C Company repositioned itself, moving and digging bigger foxholes as rumors of a German attack spread through the ranks. A false alarm set off the whole company, but no Germans were found except for a small scouting party. Over the next several days, the company sent out a few small patrols to try and prod for German positions, with little luck.

On the fourteenth, C Company replaced elements of the 502nd’s 2nd Battalion as the regiment split into three “phase lines.” The three lines staggered one after another. The battalions of the regiment would each be tasked to hold a line for three or four days before the entire regiment would shift, evenly balancing who was required to sit up front in the most dangerous positions. Yates, having been up front for the early part of the month, went to Aldtest, near an apple orchard, which sat in the middle of the middle phase line. This area was not quite as dangerous, with more cover around, but still well within the German firing range should someone step out of line.

Patrolling 502nd paratroopers on "the Island." From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

Yates joining C/502

The award of Yates' Combat Infantry Badge by C/502

Patrolling 502nd paratroopers on "the Island." From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

C Company’s turn to go back to the front came on October 17, where they once again crawled into frontline positions near a dike. At this point the Germans had retreated towards the distant Rehenen Bridge, but their artillery was still well aware of the American presence. The troopers of C Company greatly feared the German guns which controlled their movement. Since one could only move during the night, sleep was secondary to keeping an eye out for any German patrols. Artillery duels thundered around them during the day, while each pair of paratroopers sat in their foxhole, building off of each other to simply make it another day

The company went back to the rear on the twenty-first, getting to spend eight days recovering until they were back on the frontline. At this point, they were in positions way out in no-man’s-land. The weather was quite chilly in the late fall air, and C Company was responsible for a number of phone lines used to communicate with the rear areas. While in these positions, the men saw their first German jet planes as a pair of ME-262s soared high overhead.

The back and forth of the phase lines continued for nearly the entire month of November, with C Company doing its part to rotate in and out of ever-more hazardous conditions to secure the sector. German troops rarely appeared, however, and their greatest enemy continued to be the ever-present artillery bombardments. During this period, Yates was awarded his first decoration: the Combat Infantry Badge. To recognize his service in combat since Market Garden began, C Company put him in for the decoration. Unfortunately there was no time to celebrate as they continued on in their defensive slog. Thanksgiving was spent in frontline positions, a rather poor situation to encourage thankfulness.

On November 27, C Company was finally given the orders to mount up on trucks and cross the Waal River. After two months suffering through the Island, the men were given ten days off in Reims before heading to the large military base at Mourmelon, France, to rest and recuperate. Yates only got to enjoy a couple of days of freedom before getting sick in early December, rejoining the company from the hospital on December 10.

An average 502nd foxhole in Holland. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

A standard view from one a 101st Airborne position on the Island. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

A farmhouse occupied by the 502nd on the Island. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

An average 502nd foxhole in Holland. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

Unbeknownst to the paratroopers, just a week later their rest would come to an end. In the early morning of December 16, 1944, roughly 400,000 German troops and over 1,100 tanks began pushing through the dense forests of the Ardennes directly into the American lines. The attack was a total surprise and American defenses quickly collapsed as battle-weary or inexperienced units along the front fell apart. Within hours, the frontline had been pushed back for miles and the famous “bulge” in the line was already beginning to form.

Two days later, on December 18, the men of the 101st Airborne Division were notified of this major offensive and warned to gather their gear for immediate redeployment. Yates and the rest of C Company loaded up on trucks and began the trek to Belgium. Their objective was the city of Bastogne.

Bastogne was a large town in the middle of the Ardennes sector. Most critically, it was a key hub connecting many major roads throughout the region. It was thus essential to keep the town out of German hands. With German forces rapidly approaching, the 101st Airborne was assigned the task of taking and holding the city no matter the costs. Unfortunately, in the rush to get the division into the city, there was not enough time to equip the men with proper winter uniforms, gear, ammunition, food, and other essential supplies. Nevertheless, the troopers would grab whatever was available and take it with them, hoping that in the following days they might be resupplied to keep up their defense. C Company, and most other units of the division, also had yet to recover their manpower from the losses in Holland. C Company alone was only operating at a strength of around 130 men.

Undermanned, underequipped, and outnumbered, each unit of the division took up its assigned sector around Bastogne, with the 502nd receiving the north and northwest portions of the line.

The winter was proving especially cold, as swirls of snow, sleet, and biting wind blew past the convoys of paratroopers while they moved under the cover of darkness. Their first night in Bastogne was spent camping along a roadside near the village of Long Champs, which soon became one of the focal points of the 502nd line of defense. On the morning of the nineteenth, C Company reached its final positions near a hill south of Long Champs overlooking the town. The 502nd was slated to serve as division reserve for the initial days of the operation.

Map showing the first days of the Siege of Bastogne.

502nd men leaving Mourmelon for Bastogne. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

Map showing the first days of the Siege of Bastogne.

Various units of the 101st began combat operations on December 20, with C Company moving into the 506th Parachute Infantry area to act as a reserve unit west of Foy while the 506th and other companies of the 502nd attempted to take the town. Yates and his comrades were dug in along a winding hillside road next to the small town, and were on occasion subject to enemy tank fire. At the same time, the entire division became surrounded. German forces had worked around their envelopment of Bastogne and cut off all seven major roadways into the city. The paratroopers were trapped.

Around 0730 the next morning, they marched off once again to help G Company of the 506th for its attack on Recogne. The C Company troopers plowed through the snow all day until they reached G Company on top of a wooded hill, digging their own foxholes nearby to bolster the position. That evening they were told they could move to the rear once again. The next day continued the snowy marching as C Company moved to a wooded hillside along a main road two miles east of champs, where they were fortunate to receive their first hot meal from division as freezing heavy snow fell around them.

The next two days took the company to Hemroulle, a village behind the lines of the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment on the west side of the encirclement. Word had come through that elements of the 26th Volksgrenadiers had broken through the 327th and that there was a serious threat of a total collapse. Yates and the rest of C Company also wondered when they might finally be sent into action. Like the snow, rumors swirled around them, as passing troopers told stories of heavy combat all across Bastogne putting the division to the test. The company surely felt somewhat silly when they received extra supplies of ammo, medical supplies, gas, and other equipment, when they had not even seen combat yet. Even without directly witnessing the fighting, the waves of C-47s overhead on their way to airdrop supplies in Bastogne proper signaled the seriousness of their situation.

502nd troops near Long Champs. From the collection of Paul Adamic.

A C/502 foxhole near Longchamps. From the collection of Gary Martin.

502nd troops near Long Champs. From the collection of Paul Adamic.

C Company’s Christmas was not very merry.

In the dark of early morning on Christmas, C Company was ordered to move up to support the regimental frontlines, traveling the road from Hemroulle to the edge of Champs. Orders were to wait for daylight before moving in to help A Company, as German soldiers had broken through the lines of the 2nd Battalion, 502nd Parachute Infantry, to their east. The company took a few hours to move the half mile up the road, as the men were draped in their full “battle rattle.”

Thick wool overcoats were the primary source of warmth for the troopers since they lacked winter boots, sweaters, hoods, or any other meaningful equipment to combat the stinging cold. After reaching a small farm that contained the command post of 1st Battalion, 401st Glider Infantry Regiment, the men started fires, made coffee, and watched a distant dogfight between aircraft overhead. Little did they know, the 401st men inside the farm were in the process of burning maps and papers to evacuate the position.

As daylight broke, fog covered the landscape. The men had just begun lazily moving off the road when voices rang out into the misty dawn: “GERMAN TANKS!” Several hundred yards away, across a snow-covered field, around eighteen whitewashed Panzer IV tanks and three STuG III assault guns were topping a hillcrest leading up to the farm. German infantry, wearing snowsuits and heavily armed, rode atop and marched beside the tanks. The Germans were from 1st Battalion, 115th Regiment, 15th Panzergrenadier Division, and had been tasked with attacking more weakly defended areas of the line, near Hemroulle and Champs, for a prospective Christmas breakthrough. While some were fanning towards the north and south, a contingent of seven Panzer IVs and supporting infantry began focusing their attention directly on C Company and the command post.

Map of the initial German assault on C/502. Created by author.

Overall strategic map of Bastogne on Christmas Day

Map of the initial German assault on C/502. Created by author.

Yates and his company-mates were frozen in terror. Within seconds the shock wore off and the entirety of C Company broke full speed towards a thicket of fir trees over a hundred yards behind the farm as the Panzers opened fire towards the command post, striking one of the company’s machine gun teams and blasting the farmhouses. It was a total madhouse dash with some men dropping weapons, helmets, and other gear as they ran for their lives for the protection of the trees. Some decided to try and stay back to defend the farmhouse, but the metal monstrosities, peppering the Americans with a mist of machine gun fire, proved ample encouragement for them to rethink this mindset. Other paratroopers were petrified by the sudden engagement, and were pinned to the ground.

Within minutes the Germans reached the command post, taking the GIs left behind prisoner and policing the area with confidence in their successful assault. Four of the Panzers parked right alongside them. A fire was growing on the roof of one building, while some of the Panzergrenadiers began warming up by fires in the courtyard and opening tins of breakfast.

In the meantime, C Company was beginning to rally in the woods. While the men were running up a long hillside past the tree line, the company commander, Captain George R. Cody, began waving his arms shouting for the disoriented paratroopers to “Hold up there!” and “Turn around!” “We are going back and fighting the bastards!” he shouted. NCOs took charge of the men, gathering Yates and the other survivors for a counterattack. Unfortunately, most of their heavy weapons, like machine guns or bazookas, had been left behind at the farmhouse during the rout. The company spent roughly an hour reorganizing while the Germans simply wandered about the farmhouse, waiting for additional infantry support.

As C Company was preparing to make their attack, two M-18 Tank Destroyers from the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion appeared to the right of the company. A morale booster to the troopers distraught by the German armored force, the Hellcats slowly made their way forward through a firebreak to an advantageous firing position along a ridgeline in the woods.

Around 0850, the German troops, anxious over their missing infantry, began to make their move. The three STuGs began moving northward towards Champs, where a battle soon broke out between them and another set of tank destroyers. After all the STuGs were destroyed, and both American destroyers knocked out, the four Panzer IVs at the farm began to also move northward along the treeline. Little did they know that C Company was hugging the treeline as well in wait for their counterattack.

A painting depicting C Company's counterattack on the German tanks on Christmas Day. From "Battle of the Bulge 1944" by Osprey Publishing

"Lustmolch," one of the Panzer IVs which originally attacked Yates' company. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

Likely one of the Panzer IVs from the Christmas Day battle, taken afterward.

A painting depicting C Company's counterattack on the German tanks on Christmas Day. From "Battle of the Bulge 1944" by Osprey Publishing

As the tanks moved out, C Company opened fire all along the line of the woods, pouring into the German tanks and infantry with everything they had. To the Germans, hundreds of flashes filled the forest in front of them. A huge firefight broke out between the paratroopers and the German infantry while the Panzers, slightly up the road, tried to turn their turrets and fire into the treeline with high explosive shells and machine gun fire. Although they did rake the trees, sending splinters everywhere, the troopers were hugging the ground and made difficult targets. The Americans, however, were making good work of the infantry caught out in the open away from the farmhouse and missing their tanks, which were still driving northward as the American counterattack progressed. Only one of the tanks managed to turn around, dashing towards Hemroulle.

At the same time, the two M-18s in the forest and a new group of paratroopers coming in from the north joined in the fray, trapping the German armor and infantry in the white fields devoid of all cover. The Panzers only rushed away faster, leaving more of their infantry exposed and subject to the brutal fire coming from the Americans. American mortars also reached the scene, sending over 100 rounds onto the farmhouses and any remaining German infantry inside. This caused the last group of Germans to scramble from the structures, running madly across the open field. Bazooka and rifle rounds streaked from the trees as Yates and his comrades put an end to any German brave enough to try and fight back.

The M-18s made short work of the Panzers. While C Company took care of the infantry, the two destroyers opened up on the exposed flanks of the Panzer IVs heading northward. Working up the line from left to right, the crews took out each Panzer in succession, leaving four burning hulks in the snow. The German Christmas offensive was no more.

A map showing C Company's counterattack against the German assault group. Created by author.

One of the STuG IIIs which assaulted the 502nd on Christmas Day. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

German prisoners in Bastogne. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

A map showing C Company's counterattack against the German assault group. Created by author.

Yates and the other troopers from C Company slowly made their way from the treeline towards the piles of bodies now littering the field they once inhabited. Any German survivors quickly surrendered. The C Company men who had been captured in the initial attack were thankfully still there, stuck in one of the farmhouses by their captors. Now freed, they all collectively brought together the German prisoners and wounded into a collecting point. All around them lay twisted German bodies turning the snow red with blood. Smoke rose high into the air from the former Panzers. The final body count for C Company’s counterattack included thirty-five prisoners and sixty-seven Germans killed. For the entire day’s actions, C Company had two men killed and seven wounded in action.

Rather than refortify the very-damaged farmhouses, C Company began digging in along the treeline to prepare for any other possible German attacks. Taking stock of their prisoners and supplies, C Company celebrated its victory with coffee and a dinner of rations.

The paratroopers remained in their positions throughout the next morning, leaving after noon towards the 502nd command post in Rolle. There they were put into a wooded area along a hillside overlooking the valley leading into Rolle. Covering the foxholes with branches and wood, the men took comfort in their somewhat prepared positions after the hectic battle over the farmhouses. The company spent three quiet days in the holes, with the most excitement being news that the 4th Armored Division had broken through somewhere to the south.

On December 28, C Company moved back to the frontlines at Champs just southwest of A Company. Shortly after leaving a wooded area and entering an open field on the way to a crossroad, a German machine gun opened up and pinned down the entire company. It took some time to finally knock out the gun and reminded the men of the precarious situation still present all around Bastogne. That evening, they dug into a hillside outside of Champs which marked the forward most lines of the 502nd.

C Company men in Long Champs. From the collection of Gary Martin.

A knocked out Panzer IV near Bastogne.

C Company men in Long Champs. From the collection of Gary Martin.

Over the next four days Yates and the rest of C Company made themselves comfortable, holding the line from German patrols and probes. With German troops only a few hundred yards away, scattered firefights and artillery proved a constant threat along with the very real fear of another German assault. 88s and mortars would periodically pound into their positions, sending treebursts, shrapnel, and snow throughout the air around them. German infantry movements mostly came at night, but flares and fires made sure that they would not try to sneak any surprise attack.

New Year’s Day was welcomed with the flashes of opposing artillery as fire from both sides lit up the lines. As day broke, C Company spread out some of its men towards the edge of Champs since German forces were still attempting to press the line in different areas. Around this time, another dangerous enemy was starting to cause problems in C Company and across the entire 101st Airborne: the cold. After nearly two weeks of fighting from frozen positions clothed with insufficient gear, men began suffering from frostbite left and right. Trench foot became a prevalent problem and day by day more men were forced to leave the line for treatment. New Year’s did bring some relief, as sets of warm winter clothing and underwear finally reached C Company. For many, however, it was too late.

The company left Champs and returned to Long Champs the next day, taking up positions in houses as they held the town. German artillery was the primary opponent during this period. On January 6, hot showers and laundry were brought up to give the men some reprieve before their planned move out of the town. The next morning they made their way back up to the frontline near Champs, digging a series of complex and fortified foxholes using wooden boards to provide support and roofs. Tragically, the persistence of the German artillery led to the deaths of four C Company troopers that day.

Yates’ time in Bastogne then came to an end. On January 8, an intense blizzard filled the air with heavy snowfall and wind. Visibility was poor and snow began filling into the well-constructed positions of the company. Temperatures at this point were around fifteen degrees fahrenheit, with a wind chill below zero. Although German infantry were not in sight, the artillery and elements were taking their toll. The storm continued into the next afternoon as Nebelwerfers struck the company’s segment of the line. This was their twenty-third day in the Bulge.

Unfortunately this was also the end of Yates’ participation in the defense of Bastogne. Like many of his comrades, he too had been suffering from the intense cold and snow. Also lacking proper winter equipment, he had developed a severe case of trench foot which had reached the point of debilitating him. He was evacuated to a clearing station and eventually to a field hospital to recover alongside many similarly situated paratroopers. As Yates healed from his injuries, the defense of Bastogne turned into a counteroffensive, driving the German forces back, ending the siege and the Bulge.

A 502nd machine gun team near Champs. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

A good example of the improved foxholes made by the 502nd at Bastogne. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

C Company morning report mentioning Yates' hospitalization.

A 502nd machine gun team near Champs. From "The Screaming Eagles in World War II" by Mark Bando.

Yates made a full recovery and rejoined C Company on February 9, 1945. After his absence, the company moved with the rest of the division to the town of Haguenau in Alsace. Much further south than they were before, the 101st Airborne was retasked to support Allied operations in Alsace after Hitler launched Operation Nordwind, a smaller offensive south of the Bulge intended to divert American resources. Haguenau, just north of Strasbourg, was a central city in the area affected by Nordwind. By the time the paratroopers arrived, the city was mostly within Allied hands, and defensive lines had been set up on both sides of the bordering Moder River. While the 506th and 501 were more in the city proper, the 502nd was set outside the western edge of the city, digging their foxholes in the farmland abutting the Moder. On the other side of the fast-flowing water, Germans dug positions in the treeline of an extensive forest.

Throughout the month of February, Yates and the men of C Company took turns between sitting and watching from their foxholes and embarking on dangerous patrols across the river to test the German lines. Even amidst the chilly weather, nightly patrols braved the icy water and sought prisoners, intelligence, or simply some form of engagement with enemy forces. It was not as bad as what they had experienced in Holland and Bastogne, but still kept the men on their toes. At the same time, the company has yet to replenish itself from Bastogne and was operating at a less-than-optimal strength.

On February 23, 1945, C Company moved back to Mourmelon, France, for a month-long rest where they could finally recuperate from the losses in Bastogne and Haguenau. By April 2, they were once again on the move, traveling to the Ruhr to hold yet another defensive line along the Rhine River near Dusseldorf and perform military government duties. This was not the same type of defense they had previously experienced, however, as they got to stay in civilian homes and enjoy the amenities of local life. They were there to be a presence, more so than an occupying or attacking force. USO shows, alcohol, and passes to visit other European cities provided entertainment for the men. The only German presence came in scattered artillery which sometimes hit nearby.

Yates did manage to enjoy some of his time amongst the people of Germany. On April 17, he was sent to the hospital for gonorrhea, likely picked up from a more than generous local.

Yates, on the left in the group of four, with some buddies, likely in Alsace.

A photo taken by Yates of a friend in jump gear.

Yates, on the left in the group of four, with some buddies, likely in Alsace.

He rejoined the division a week later as the entire division moved to Bavaria for an advance into the mountains of Austria. Fears over a “national redoubt,” a German plan to move troops into the mountains for a final stand, led to the division’s reassignment to support a quick drive into the heart of southern Germany and break any hopes of any more war. Driving along in their trucks, it became clear that the war was at its end. German prisoners began flowing in streams and much of the paratroopers’ time was spent billeting and enjoying the contents of civilian homes.

While high in the alps, the news finally came on May 7, 1945, that the war was over. All German soldiers in the area were to surrender and all American forces were to hold in place. Yates had made it through.

The 502nd moved to the village of Kempton, near Berchtesgaden, with the primary job of receiving and organizing the nearly 15,000 German prisoners who surrendered to the 101st. C Company remained in this area with the rest of the regiment until July, when they moved deeper into Austria near Uttendorf and, at the end of the month, back to Auxerre, in France. Occupation duty was a grand relief to paratroopers like Yates who had gone through hell at places like St. Oedenrode, Champs, Haguenau, and elsewhere. Training did set back in for the division after it was announced that they were slated to travel to Japan for the inevitable invasion in the still-ongoing Pacific War. As part of this process, Yates tested and qualified for the Expert Infantryman Badge, alongside his Combat Infantryman Badge, which was awarded on September 26, 1945

Yates' award of the Expert Infantry Badge

Yates' award of the Expert Infantry Badge

He rejoined the division a week later as the entire division moved to Bavaria for an advance into the mountains of Austria. Fears over a “national redoubt,” a German plan to move troops into the mountains for a final stand, led to the division’s reassignment to support a quick drive into the heart of southern Germany and break any hopes of any more war. Driving along in their trucks, it became clear that the war was at its end. German prisoners began flowing in streams and much of the paratroopers’ time was spent billeting and enjoying the contents of civilian homes.

While high in the alps, the news finally came on May 7, 1945, that the war was over. All German soldiers in the area were to surrender and all American forces were to hold in place. Yates had made it through.

The 502nd moved to the village of Kempton, near Berchtesgaden, with the primary job of receiving and organizing the nearly 15,000 German prisoners who surrendered to the 101st. C Company remained in this area with the rest of the regiment until July, when they moved deeper into Austria near Uttendorf and, at the end of the month, back to Auxerre, in France. Occupation duty was a grand relief to paratroopers like Yates who had gone through hell at places like St. Oedenrode, Champs, Haguenau, and elsewhere. Training did set back in for the division after it was announced that they were slated to travel to Japan for the inevitable invasion in the still-ongoing Pacific War. As part of this process, Yates tested and qualified for the Expert Infantryman Badge, alongside his Combat Infantryman Badge, which was awarded on September 26, 1945

Yates' interview and photo in "The Screaming Eagle Newsmagazine"

Yates' interview and photo in "The Screaming Eagle Newsmagazine"

With the dropping of the atomic bombs and end of the war as a whole, men began leaving the 101st in droves. Those who had sufficient “points” were given priority while others, like Yates, had to stay behind, yearning for the day they would finally reach America after years of war. In late September, Yates was interviewed by one of the division’s combat correspondents for a piece in the division magazine “Screaming Eagle.” The interview asked a few random men from the division what they planned to do once they got home. Yates was selected to represent the 502nd, and said as follows:

I’m going to get back to Harrodsburg, Kentucky, and literally do nothing for a couple of weeks or a week at least. Then off to Louisville to see the girlfriend. Nothing like marriage just yet, mind you.

Interestingly, the individual picked to represent the 506th in the interviews was Private Ralph Spina, medic of Easy Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment. His photo and statements are directly beside those of Yates.

On December 27, 1945, just over a year from his precarious battle with the German Panzers near Hemroulle, Yates finally came home. He landed in New York harbor and took a train back to his old Kentucky home, receiving his formal discharge from the U.S. Army on January 4, 1946.

Yates, driving the dozer, while breaking ground on Mary & Elizabeth Hospital in Louisville, Kentucky.

An article in The Courier Journal announcing Yates' marriage to Christine.

An article from 1946 describing Yates' bus-driving antics.

Yates, driving the dozer, while breaking ground on Mary & Elizabeth Hospital in Louisville, Kentucky.

He also made good on the promises set forth in his interview, visiting his family back in Harrodsburg before returning to Louisville to see his beloved Christine. In May of 1946 they were married, settling in the Shively area while Yates took up the first of several jobs in industry, first as an enameler and then as a bus driver for the Louisville Railway Company. This job did not end so well, as he was caught racing another driver with two empty buses at forty-five miles per hour right down Broadway.

In 1947, Yates’ first child, a daughter, was born and he began working as an inspector for the Reynolds Metal Company at its large aluminum plant in Louisville. He stayed here for a few years before having a second child, a son, and hopping careers to work once again in construction, this time for the John Wile Construction Company as a heavy machinery operator. In 1956 Yates was prominently featured in the Courier Journal working in this position, riding a dozer during the groundbreaking for what is now the University of Louisville Health Mary & Elizabeth Hospital.

By the 1960s, Yates grew tired of busy industrial life in the big city and set out to pursue his old family profession of farming. He and his family bought a small farm in Milltown, Indiana, not far from Louisville, and started a cattle farm. He remained regular in Louisville, however, as he primarily sold his cattle at the city stock yards. Still proud of his service in the 101st Airborne Division, throughout his professional career he remained active in his local VFW. After retiring in the 1980s, he moved back to Kentucky, buying a home in Lebanon where he lived out the rest of his days. Outliving his wife and brothers, and with his children settled in distant states, he passed away at his Lebanon home on July 22, 2003.

Yates' military artifacts returned to his grave in Lebanon, Kentucky.

Yates' military artifacts returned to his grave in Lebanon, Kentucky.

Yates' obituary.

Yates' military artifacts returned to his grave in Lebanon, Kentucky.

Source Material:

--The Last First Sergeant by Layton Black

--No Silent Night: The Christmas Battle for Bastogne by Leo Barron and Don Cygan

-101st Airborne: The Screaming Eagles in World War II, Mark Bando

-Original Unit and Personnel Records

-Various Newspaper Sources

-Veteran Interviews

-Epic of the 101st Airborne: Pictorial Biography of the United States 101st Airborne Division