_edited.png)

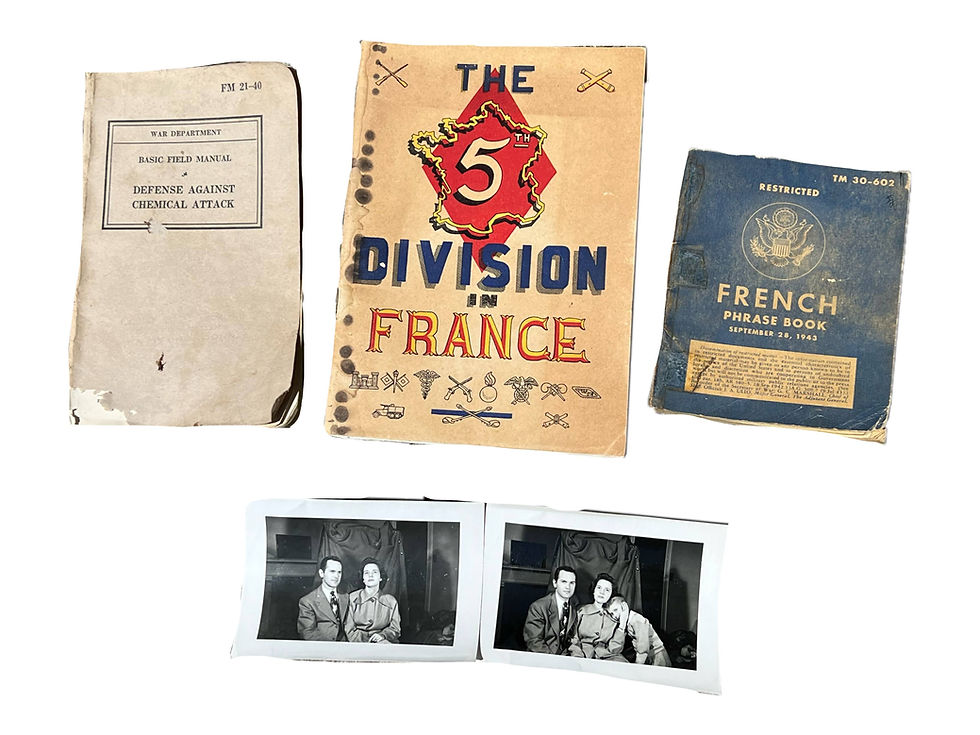

The 36th Division Archive

Captain Charles M. Hoge

Battalion Communications Officer, Battery Commander

HQ Battery, 46th Field Artillery Battalion, 5th Infantry Division

Charles Mason Hoge was born in October 1918 to a well-known and successful Frankfort, Kentucky family. The Hoges were a prominent family amongst the local population, as they founded and headed the Hoge-Montgomery Shoe Company, a large manufacturer of women’s and children’s shoes located within the Kentucky capital. With his father working to manage and oversee the booming company alongside other family members, they were fairly well-to-do with a fine stone home located right in the heart of downtown, only a few blocks away from the capitol building. It was here that Hoge grew up. In 1932, however, things took a turn for the worse as the effects of the Great Depression forced the shoe company to close down and, in 1938, it was sold off. Even so, the many members of the family who had worked there were comfortable with the profits.

While his parents retired, Hoge had to find a career for himself. Interested in potential military service, he applied and was accepted to the Virginia Military Institute in 1936, the alma mater of several of his uncles. Although the academy did not rate him highly for his academics, he had high marks for his intellectual promise and personal character, earning him entrance. While at VMI he was well-liked by many of his classmates and described as a “great patriot to his native state and to the South” further explaining that in case of dispute, “he will argue any time in defense of either.” He did not rise to the command ranks of the cadets but instead was happy with his studies and participation on the wrestling team. He graduated in 1940 with a degree in civil engineering and returned to Kentucky where he officially joined the United States Army as a second lieutenant in the artillery.

Hoge was attached to the 21st Field Artillery Battalion of the 5th Infantry Division, one of the few national units, which was being reorganized and brought back to strength as tensions worsened across the globe. First stationed at Fort Knox, he moved with the unit to Fort Custer where they stayed following the attacks on Pearl Harbor until the entire division was slated for transport overseas. Hoge eventually sailed from New York in May 1942, joining his new unit, the 46th Field Artillery Battalion, in Iceland later that month. Here units of the 5th Infantry Division spent almost an entire year protecting the island from feared German attack. As American units began preparing for an inevitable war in mainland Europe, however, Hoge and the division moved to the British Isles in early 1943, traveling to England and then northern Ireland where they began continual training preparing for the eventual invasion.

In July 1944 the time of the division had come. A month after Allied troops landed on the beaches of Normandy, the 46th Field Artillery Battalion waterproofed their guns and vehicles and sailed out of Belfast towards France on July 6, 1944. How the battalion communications officer and the Commanding Officer of the HQ Battalion, Hoge led his men off the boat onto Utah Beach on July 9, disembarking at 0115 in the dark before making a 17-mile foot march to the 5th Infantry Division assembly area near Montebourg. Far from the safety of green-clad Iceland or the rocky Irish coast, Hoge and the battalion now found themselves in the thickest fighting in Europe. Replacing elements of the 1st Infantry Division on July 14, the 46th Battalion was attached to their war-long battle buddy, the 10th Infantry Regiment, where they held their baptism of fire against German panzergrenadiers in the Normandy hedgerows.

The fighting was fierce as enemy tanks, self-propelled guns, vehicles, and infantry hit hard against the division’s lines. The 46th had its first casualties only a few days into the fighting when one of their grasshopper spotter planes was shot down behind German lines. As the battalion communications officer, Hoge was in charge of maintaining the channels between the infantry and forward observers with the gun batteries to the rear. This meant many trips to the frontlines, often spent repairing destroyed telephone wire, servicing radio equipment, and ensuring all required artillery assistance was able to be given when needed. As the commander of the HQ Battery, his secondary role was to oversee all the logistical side of the battalion’s operations, from calling in fire directions, maintaining communications, coordinating movements and attacks, and much more.

In Normandy, Hoge and his men saw daily combat with positions close to the frontlines launching constant fire missions to support the infantry’s grinding battles between the heavily-wooded hedgerows. On July 20 the battalion first changed its target to spend a week firing thousands of rounds in support of the 2nd Infantry Division which was making a large attack on a nearby German position. The artillery proved so dangerous that the Germans even sent six planes to strafe the artillerymen. Thankfully, their AAA gunners shot down five, and no casualties were taken. From July 28 through the rest of the month, the battalion went back to supporting the 10th and 11th Infantry Regiment’s offensives operations, again consisting of heavy hedgerow fighting. Observers on the ground were highly limited during this period by the nature of the wooded turf and aerial observers struggled with the same difficulties. Regardless, they maintained constant pressure on the German forces to ensure American troops could make the breakout from Normandy.

The month of August found Hoge’s logistical talents put to the test as the battalion joined the many American units breaking through German positions and driving through France. Traveling a total of 613 miles inland, the artillerymen moved alongside the 10th Infantry Regiment to support their large but combat-inundated drive into the countryside. August 9 found the first major combat of the month when the battalion provided fire support for a major river crossing near Angers, firing over 3,000 rounds on 97 fire missions against German targets. On August 10 the battalion even captured its first prisoner, although he was not even German; rather, he was a Russian prisoner put into military service who had been sent to guard the French coast. Upon a successful assault, the unit continued forward, providing numerous fire missions against a determined and well-equipped German foe at places like la Chapelle and Monterau, where they crossed the Seine River. Units faced throughout this period were both regular German army grenadier units as well as elements of the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division. According to the unit journal, “the battalion was constantly on the move” between missions as their infantry was tasked to the advance guard of the division. It was a massive game of highly-explosive chase.

In early September the drive came to a slow as the 5th Infantry Division became wrapped in battles near Avocourt, east of the Argonne Forest. It was here, however, that now Captain Hoge was first decorated for his distinguished service in overseeing the operations of the 46th Field Artillery Battalion. Awarded one of the first Bronze Stars for the entire unit, his citation read:

“Captain Charles M. Hoge, 0389304, 46th Field Artillery Battalion, United States Army. For meritorious service in connection with military operations against the enemy from 4 August 1944 to 3 September 1944 in France. Captain Hoge was a Battery Commander during this entire period. The Battery traveled 763 miles and participated in six engagements with the enemy. No vehicle was lost due to mechanical failure and all vehicles were accounted for after each day’s march. All positions were occupied efficiently and rapidly which enabled the Battalion to be prepared to deliver fire in support of the infantry in the shortest possible time. In some instances the Battery was sent on separate missions and under some instances the Battery was sent on separate missions and under such circumstances conducted itself in an excellent manner. The successful operations of the Battalion was made possible by thorough briefing and constant checking of small details by Captain Hoge within his Battery. Due to Captain Hoge’s leadership and devotion to duty his battery contributed immeasurably to the successful advance of the combat team which the Battalion was a part. His actions reflect great credit on himself and our armed forces. Entered military service from Kentucky.”

After these decoration-deserving actions, Hoge and the battalion were not given time for a rest as the drive continued onward, beginning a campaign along the Moselle River on September 7 near Metz. The entire period was spent once again shelling German targets that plagued infantry operations, primarily tanks, infantry and gun positions, and convoys. On the 17th the battalion finally crossed the Moselle only to find themselves once again in extremely close, hazardous combat. Attempting to push highly-determined German forces back from the river, at one point Hoge was within 1330 yards of the enemy, becoming the target of German mortars as they sought to do everything to hold off the Americans. The German forces were eventually pushed back, however, and by October the division had settled into a defense line around the area. The only offensive actions taken during this period were the taking of Fort Driant, overlooking the area, but for the most part, both sides began to dig in and patrol the region to secure their respective parts of the line. By the end of the second week of the month, Hoge’s men had constructed elaborate gun pits and fortifications, including dugouts for the troops, guns, and vehicles. Fire missions were mostly sporadic against spotted targets, enemy patrols, or counter-battery fire. With the stagnant nature of the fighting, most of Hoge’s concerns came in the maintenance of the telephone wire which was the exclusive method of communicating with the different batteries and infantry units. These were often damaged by enemy artillery fire and as such Hoge had to ensure their operation for the successful defense of the line. By October 21 the division was rotated out for a training period, and a little rest, where they spent ten days in Xivry-Circourt training replacements, repairing gear, and enjoying any free time they could find.

In November the men moved back to the front for continued operations against Metz, spending the first ten days of the month using logs, railroad ties, scraps from destroyed buildings and earth-making shelters and gun pits for their crews. The Germans were back with a heavy artillery presence, engaging in duels with Hoge’s men as well as tearing apart the surrounding area. Once the attack of the division began on November 10, however, the 46th was back in action. Stationed near Fluery, the 46th sent thousands of rounds towards the fierce German forces, fighting village to village, causing massive amounts of casualties in the hazy November forests. In fact, the battalion became so notorious for its skill and accuracy in knocking out German positions, a captured German artillery officer by the 10th Infantry Regiment claimed he stopped using a car entirely to travel between his gun batteries, instead opting for a bicycle as his car’s engine often attracted accurate American artillery. The mass fires of the battalion with others nearby caused many of the lower-grade German troops to break and run, allowing the division to push forward and up to the Maginot Line near Niedervisse.

Early December found the 5th Infantry Division pressing on this advance to break the Germans near Metz. High-quality German troops once again entered the scene, Hoge and his men supported a combined force of the 10th Infantry Regiment, 5th Rangers, and 6th Cavalry Recon Group as they fought to push back the Germans near the border at Uberherrn. The battles consisted of around 25-30 daily fire missions against enemy posts, spotted movements, self-propelled guns, counter batteries, and more. It was a busy time for the unit as consistent fire support was a necessity. On December 17 they moved to Schonbruck to fire on several key bridgeheads faced by the division, only to move nearly 80 miles a few days later to Ernster, past Luxembourg, to prepare a second defensive line behind the division. The last ten days of the month were spent supporting the 10th Infantry once again across German and Luxembourg with the gradually creeping goal of Metz. For its efforts, the 46th Field Artillery was rewarded on Christmas with a report from the 10th Infantry, which had advanced into new areas, claiming they found hundreds of dead Germans that had been killed directly from their artillery fire. Santa’s christmas gifts to the krauts seemed to have come in Hoge’s 105mm shell casings.

While the rest of the U.S. Army was pushing back the Germans in the Bulge to the south, Hoge and his artillerymen spent January 1945 finally moving against the Seigfried line. On New Year’s Day, while near Ermdorf, the battalion spent their time whitewashing the guns and vehicles of the battalion as several inches of deep snow covered the landscape. With the first weeks of the month containing mostly static fighting, camouflage, and position safety were essential. Most fire missions occurred at night when the enemy could be seen moving across the snow while during the day, patrols and saboteurs were the bulk of the battalion’s problems. On January 18 the offensive picked up once again when the 10th Infantry Regiment crossed the Sauer River near Bettendorf, requiring artillery support from the 46th. Heavy enemy counterfire drew the battalion into artillery duels but as the infantry pushed onward, the gun crews had to keep on the move just to stay apace with their designated troops. This advance continued into February as heavy fog, rain, and snow moved the battalion to Berdorf where they set up positions for a major attack against the Sauer River.

On February 5 the 46th Battalion moved to Berdorf, a small town near the Sauer River, to set up fire positions for the planned assault of the division across the river. In preparation for the attack, the 46th launched a massive fire plan, sending hundreds of shells hurtling toward the enemy concrete pillboxes dotting the far side of the bank. At 0130 on the 7th, the 10th Infantry launched their attack, crossing the raging river in rubber boats which, after a few minutes, mostly flipped over and drowned the weighed-down occupants. Beyond this, the enemy began launching precision strikes against the location as they had sighted it previously with artillery and machine guns. After a few attempts to cross, all failures, the regiment waited to continue until the next day to continue on. On the night of February 8-9, many men of the regiment began making it across the river, pushing forward into the opposing lines to heavy small arms and artillery fire. The artillery was especially withering, narrowed exactly upon the crossing site attempting to keep the assault troops from reaching the hard points on the other side of the river. Throughout the chaos, artillery fire from the 46th Battalion attempted to support the men, however, a major problem developed in the continual destruction of the communication telephone wire. According to one report, “wires were shot in two no sooner than laid across the river. When restringing or repair operations proved too hazardous by boat, the expedient of shooting the wire across attached to rifle grenades was used.” This problem was Hoge’s to solve.

Sometime during the crossings between February 8 and 10, Hoge, as the most knowledgeable and creative with the use of communication wires, went to personally manage the communication situation directly at the crossing point. Under withering enemy fire, his actions here earned him our nation’s third-highest decoration for valor, the Silver Star Medal:

Captain Charles M. Hoge, 0389304, 46th Field Artillery Battalion, United States Army. For gallantry in action on 7 [through 10] February 1945 in the vicinity of Weilerbach, Germany. When wire communications were imperative during bridgehead operations across the Sauer River, Captain Hoge, the battery commander, and communications officer, disregarding personal safety, succeeded in crossing the river with the assault elements under intense enemy fire. Skillfully establishing communications between the forward observers and the artillery liaison officers, Captain Hoge enabled our artillery to bring accurate, effective, and precision artillery fire upon the enemy’s positions. His technical skill, courage, and unswerving devotion to duty reflect great credit upon himself and our armed forces. Entered military service from Kentucky.

His actions proved the utter courage of both Hoge and the brave artillerymen who worked tirelessly and under extreme danger to keep the support of the infantry elements alive. By the 10th the crossing had proven a success and the infantry were making major progress inland, making it to the Siegfried line and pushing out the German forces as the 5th Infantry Division finally made their way into the German fatherland.

Frankfurt was a major target. As one of Germany’s largest cities, it was crawling with German troops ready to die for the defense of their homeland. The 10th Infantry decided to plan their crossing of the Main River, the primary obstacle between them and the liberation of the city, just north of Sportsfeld. Thanks to a map captured by the infantry, the 46th was able to preempt the assault with barrages knocking out all the major flak positions in the city and many other gun outposts. Most of the enemy were entrenched in heavy concrete and brick fortifications, meaning it took many direct hits to prove effective. On the 27th the infantry began their assault and Hoge again sought to oversee the communication situation of the battalion with the infantry forces personally. As the infantry began suffering from intense tank, small arms, and artillery from Germans trying to push them back into the river, Hoge continued on in his Weasel amphibious support vehicle bringing wires, supplies, and secure communications to the American troops. It was for his actions he was awarded a second Bronze Star:

Captain Charles M. Hoge, 0389304, 46th Field Artillery Battalion, United States Army. For distinctive heroism in connection with military operations against the enemy on [27 through] 29 March 1945 in the vicinity of Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany. When forward elements of the infantry had crossed the Main River into Frankfurt and it became necessary to install wire communications between the infantry and supporting artillery, Captain Hoge, a communications officer, with utter disregard for personal safety and in the face of intense artillery fire, crossed the river in amphibious vehicles and led his wire crew in the laying of a line, resulting in the installation of a rapid, efficient channel for transmission of fire calls. His coolness and courage under fire and his devotion to duty reflect great credit upon himself and the military service. Entered military service from Kentucky.

Thanks to his efforts, the 46th Battalion was able to provide effective fire support throughout the division’s operations against Frankfurt. Within four days the entire city was captured and countless enemy troops were taken prisoner, some quality, some simple civilian conscripts (the Volksturm).

With Frankfurt cleared, Hoge and the rest of the 5th Infantry Division were rerouted to support other areas of the line, specifically the containment of the Ruhr Pocket. Traveling many miles north, the division relieved the 9th Infantry Division to help secure a large mass of hundreds of thousands of German troops slowly being encircled in the Ruhr Valley. From April 9-15 the artillery traveled from village to village keeping up with the infantry, knocking out Nebelwerfers, artillery batteries, flak guns, vehicles, tanks, and clumps of German personnel spotted by the infantry as they traveled towards their primary objective of Holzen. It was a fast but successful campaign and saw the artillery eliminating some of the last scraps of German resistance in the war. Once they captured Holzen, the objective for the 46th and 10th Infantry, they hunkered down, creating heavy entrenchments for the guns as they awaited the surrender of the German troops within the pocket. Little did they know, but this would be their last true combat.

On April 26 they were finally relieved and moved all the way back down to Frankfurt where they supported a 4th Armored Division breakthrough intended to reach Prague. It was a huge success and the only opposition found was occasional scattered pockets of infantry who were most often very willing to surrender. While awaiting orders to advance on May 8 Hoge and his men received the word that all German forces in Europe were preparing to surrender. The war was finally over. After almost a year of grueling combat across France, Germany, and Luxembourg, Hoge, now a highly decorated and grizzled veteran, had seen his job through to victory.

Only a few days after the victory was declared Hoge was decorated for the last time with a Certificate of Merit from the commanding officer of the 46th Field Artillery Battalion for “conspicuously meritorious and outstanding performance of military duty.” For several months Hoge spent his time overseeing occupation operations with the division but by the fall of 1945 was able to return to the United States. Still proud and unwilling to put up the uniform, he decided to pursue a role in the reserves, promoted to Major in 1946, while keeping up numerous connections to old army buddies, including participation in their weddings. After marrying he took his new bride to visit Europe in 1947, most likely taking a peek at a few of his memorable war stops along the way.

Returning to Frankfort and his Kentucky home meant a new career, however, for the old war veteran. Hoge was not to let this new task put him down and soon put forth as much energy towards his civilian life as he had his military career. Learning the insurance field, he was able to eventually open his own insurance firm, Chenault & Hoge, in downtown Frankfort which still operates in its same location to this day. Along with an extremely successful career in this field, he became heavily involved in numerous other areas of local life, overseeing the local YMCA, serving on the Salvation Army advisory board, becoming a member of the Lions Club, spending time on the board of the Red Cross, receiving an appointment as director of State National Bank and even becoming Trustee of his own Presbyterian Church. Hoge was nothing if not a truly magnificent example of a civic leader, exemplifying the true meaning of the American “citizen soldier.” Putting away his uniform for a tailored suit, Hoge was a soldier, a war hero, a businessman, a leader, and a proud American. It is with honor we should remember his story and sacrifices.