_edited.png)

The 36th Division Archive

Private First Class Franklin M. Koriyama

Heavy Weapons Team

M Company, 3rd Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team

Franklin Masahiro Koriyama was born in May 1914 deep in the heart of Seattle’s bustling Japantown. His parents, Japanese by birth, immigrated to the United States only a year prior to his birth from Kagoshima Prefecture, leaving behind their family in search of new opportunities in the United States. Franklin’s childhood was fairly typical for that of an immigrant family. Growing up the oldest with three younger sisters, he was the little man of the household and matured amongst the cultural hotspot of Japantown, the hub of Japanese-American immigrant activity within Seattle. It was here that his father ran the family business, a grocery store, not far from their home. From the age that he could begin helping him out, Franklin assisted his father in the store from stocking to cutting up meat. Upon graduating high school he began this work full time and in 1939 took over the store full time when his father tragically passed away. His sisters, now marrying off and starting their own families, left Franklin to fend for himself and his mother as the threat of war loomed.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Franklin, like most Americans, was furious. Although many members of the community had come from Japan, just as many had been born in the United States and called the nation their only home, these were the Nisei. For Nisei like Franklin, the attack was a personal insult and worthy of all damnation. Sadly, not all Americans felt this way, and within days of the attack, new rules and commands from the top levels of government began hitting the West Coast to implement policies discriminating against Americans of Japanese descent. Fearful that Japanese-Americans would harbor some sort of underlying loyalty for the Japanese Empire, which had ironically just attacked their only home, government agents soon made their way into Japantown and began confiscating radio parts and anything they might consider a “weapon.” Franklin and his mother were not exempt and were raided just like many others. Beyond the seizure of their property, their liberty too was restricted as curfews for Japanese-American citizens were imposed and, on March 2, 1942, General DeWitt of the U.S. Army ordered that all locals of Japanese ancestry were to be evacuated from Seattle. While the Japanese American Citizen League (JACL) and other citizens protested fiercely, the cries fell on deaf ears. Given ten days to gather his personal belongings, Franklin and his mother scrounged what they could from their family home but had to give away almost everything. With no time to settle their affairs and no alternative beyond handing it over to the government, the Koriyamas lost almost everything. At a testimonial later in his life regarding the 1988 reparations to Japanese American citizens interned during the war, Franklin testified that they lost their grocery store, a new car, furniture, and other personal items worth close to $290,000 in today’s money.

Removed from their home by force, Franklin and his mother traveled to Camp Harmony at the Western Washington Fairgrounds in Puyallup. Quartered with many other Japanese Americans from Seattle, such as his sisters and their families, the family had no possessions and slept in a horse stall lined with straw-filled canvas bags. It was humiliating. Franklin felt ashamed, stigmatized, and utterly offended at the notion that his government saw him as disloyal, unworthy of his own home and business, and necessary to lock behind barbed wire. It was in these conditions the Koriyamas stayed until September 1942 when they were taken by rail to Hunt, Idaho for their permanent lodging. Stepping off the train into a government bus, Franklin and his mother were driven deep into the sagebrush desert outside of the town until they reached a scrappily constructed facility surrounded by barbed wire fences and guard towers. This was Camp Minidoka, a concentration camp built by the government to keep them away from other Americans and their own lives. Franklin recalled his first thoughts of the camp being “what a God-forsaken place,” a sentiment which rang true as dust and tumbleweeds covered the grounds. He and his mother were given the notation Family No. 11705A and placed into a barracks in Block XVI alongside his sister Hana and her husband, Minoru Masuda. Their living quarters consisted of a square segment of the barracks only separated by thin walls that did not even reach the ceiling. There was a total lack of privacy, no freedom of movement, and inadequate provisions for food, clothing, and furnishings. With the buildings made of poor materials, they provided no protection against the extreme desert heat of the summer and freezing winter nights. In his reparations testimony, Franklin detailed how his mother suffered severely from the confinement, as the poor food and hardship frustrated problems with her liver, kidney, and hypertension exponentially, eventually leading to her death. It was a shocking experience and one of America’s darkest moments. Franklin later said “[t]he loyalty oath for an American citizen incarcerated in a concentration camp was hard to fathom. My mother being denied the right to apply for an American citizenship was a mockery.” It was an experience Franklin would not soon forget.

Amidst the struggles of camp life, Franklin managed to find work driving a coal truck to and from the camp. While the war raged onward, one piece of bright news for the internees was stories of the 100th Infantry Battalion, a segregated combat unit of Hawaiian Japanese-Americans that had been sent to Italy, distinguishing itself in combat. Before long, their success, and a lack of troops, led the U.S. government to investigate the potential for more soldiers, this time out of their own internment camps. While Franklin and the other Nisei had thus far been designated “enemy aliens” and thus ineligible for the draft, in early 1943 Army recruiters visited the camp and announced that they sought recruits for a new Japanese-American combat unit, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Ironic as it was and surely painful to hear the call to serve a nation that had imprisoned them, many Nisei boys still felt the call to serve. The camp was largely split in half, with one side hateful that the government expected them to volunteer under these conditions and the other half believing that if no one volunteered it would only justify the government’s accusations of disloyalty. Franklin fell into the latter camp and in April 1943 officially decided to join the United States Army. His sister Hana discussed how she could “the the anguish and pain” in her mother’s eyes as her son announced his intentions to go to war. Despite many conversations attempting to convince him otherwise, and even more tears shed, “she didn’t stop him,” wrote Hana.

Prior to shipping off, Franklin was given special permission to visit Jackson, Wyoming with some other Nisei as part of an ongoing Army test on the treatment and perception of Japanese-American soldiers. Sent there in their uniforms, the boys skied and enjoyed a week of fun before heading back where on May 6 they loaded onto the second bus of volunteers from Minidoka. When they arrived at Fort Douglas, Utah, they were officially enlisted into the armed forces and assigned to Camp Shelby, Mississippi where the 442nd was being formed. From June 12 to 15 Franklin was once again given special furlough as part of the Army testing program, this time to Seattle to visit caucasian friends who remained there. In his report upon return, he described the reception as very cordial with no unpleasant incidents. When asked whether he felt conditions might be good enough to return evacuees to rural areas, he agreed. While the Army did not act on these findings for years, his experiences were included in Colonel C. W. Pence’s personal report on the treatment of his Nisei soldiers across the country while on furlough. After completing basic training Franklin was given additional education in heavy weapons, such as the 81mm mortar and .30 heavy machine gun, eventually leading to his full-time assignment as a weapons crewman in M Company, the heavy weapons company of the 3rd Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

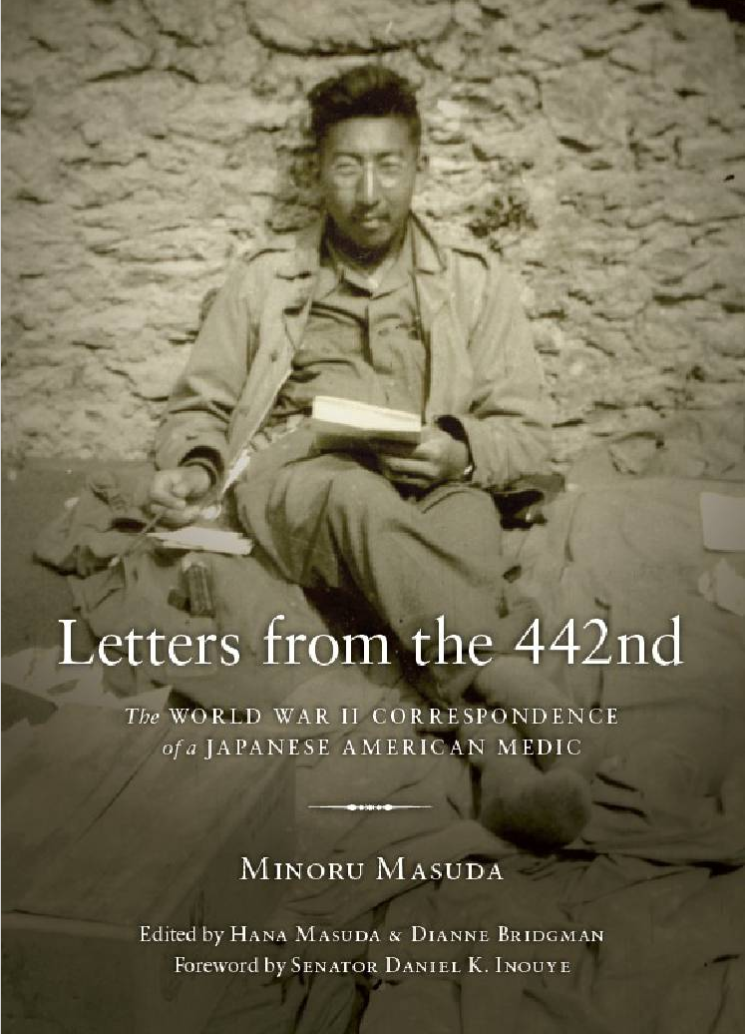

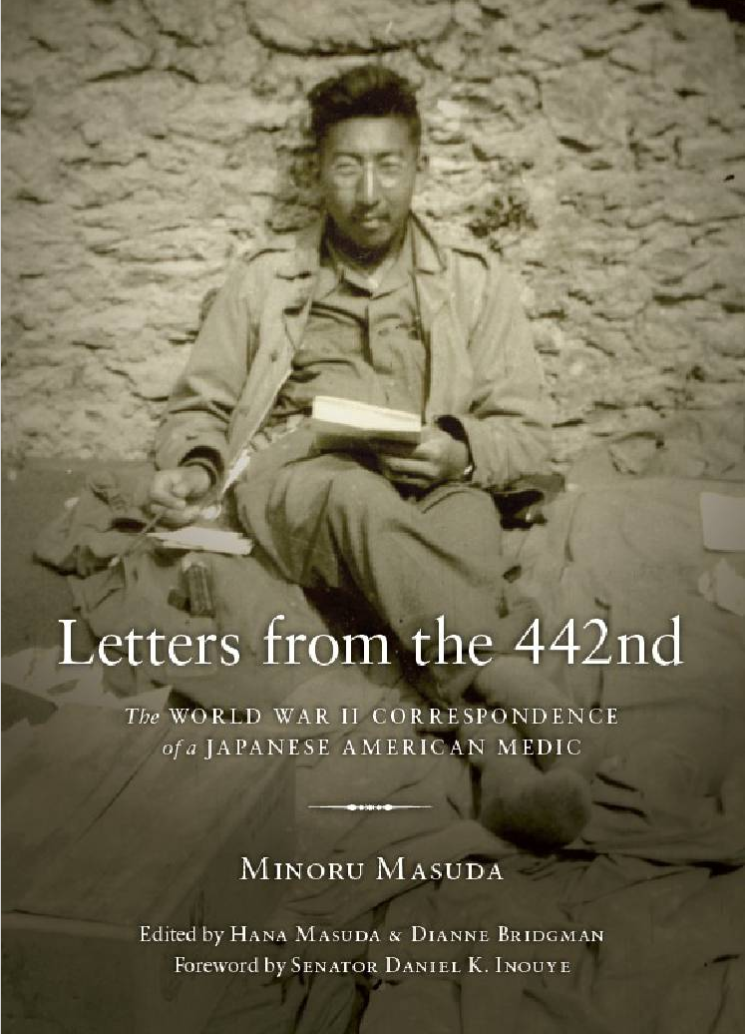

While at Camp Shelby Franklin was able to spend more time with Minoru Masuda, a combat medic in the 2nd Battalion also his brother-in-law. Minoru had married his sister after graduating from pharmacy school in Seattle and after the war became well-known for a book published containing his letters home, several of which mention Franklin himself. In one of these letters, he described Franklin as a bit more outgoing, missing church on Sundays after going out late on Saturday nights. Around Thanksgiving Franklin’s sister was given permission as a military wife to move from her internment camp to Hattiesburg, just outside of Camp Shelby, where she was able to spend more time with her husband and brother. When together both frequently discussed their mother now alone in the internment camp but hoped that the graciousness of friends would keep her going.

After nearly a year of training, Franklin and the rest of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team were sent to war, leaving the United States on May 2 and finally reaching Italy in early June. Here they joined the 34th Infantry Division, seeing first combat on June 26 by advancing through Belvedere and Sassetta as the allied forces pushed the retreating Germans north. The various platoons of M Company were split up amongst the regular infantry companies of the 3rd Battalion and sent to the far flank of the regiment near the 1st Armored Division so as to protect against a possible German counterattack. On July 1 the battalion moved to cross the Cecina River, pushing through several more small towns all the way to Colle Salvetti. At this point, the regiment’s first major struggle began over the German emplacements at Hill 140. Known as “Little Cassino,” Hill 140 was a small but heavily cragged and fortified mass. The battle here tore through the regiment for three days and Franklin’s battalion played a large part in pressuring the German troops until their surrender. For the next several weeks the 442nd moved throughout different positions as the battalions leap-frogged each other traveling northward along the Italian coastline. Amongst the major towns taken during this period were Leghorn and Pisa as the men helped drive the American advance. On July 20 Franklin was fortunate enough to get a brief furlough but was soon sent back to continue fighting near Florence, across the Arno River, and up to the Gothic Line.

On August 15, while on a brief regimental rest near Giogolo, Franklin received the very Bible featured at the top of this article. The Bible, a “Heart shield,” is one of many produced by the Know Your Bible Company out of Cincinnati, Ohio. Containing a copy of the New Testament, the Bible was supported with a gold-finished steel cover intended to protect a serviceman wearing the Bible in one of his uniform breast pockets, usually over the heart. Franklin’s mother and sisters came together to buy one of these special Bibles for him and shipped it overseas to him in the summer of 1944, arriving only on August 15. Upon opening, Franklin was able to note their signature along the giver line and followed by writing his own name and serial number above it with the date of receipt below. This Bible Franklin would carry with him throughout the rest of the war, a physical reminder of home and those who were looking out for him, both overseas and above.

At the end of August, the 442nd was relieved and notified that they would soon be traveling to a different theater. Having distinguished themselves in action, Franklin and his comrades had no idea of their future situation but nonetheless spent the time relaxing, reequipping, and teaching many of the new replacements who joined the unit. In early September Franklin’s company packed its bags and made the journey to Southern France. While Minoru complained in his letters about his own travel, he claimed Franklin had a great time as his ship contained a USO Troupe and some WACs onboard who provided plenty of entertainment to the group of young battle-weary Nisei. Arriving a week after, Minoru managed to catch up with Franklin and claimed he was “fit and fine and is the same Joe as ever.” At this point, Franklin was bothered as he had been temporarily attached to E Company, a mainline rifle unit. Minoru wrote that Franklin desperately wanted to go back to his old unit, especially because it was much safer with fewer casualties. Thankfully the transfer was only temporary and after E Company managed to fill its ranks with new recruits he was able to go back with his old men.

On October 14, after a bump and long truck ride from Southern France, all the way to the Vosges Mountains, Franklin and the 442nd joined the 36th “Texas” Infantry Division near Le Void de la Borde, marching the rest of the way to the frontline. The Vosges Mountains were composed of thickly wooded and mountainous terrain. Many large hills and valleys speckled the landscape with deep forests covering every inch of undeveloped land. For several weeks the U.S. 7th Army had been stuck trying to push through the heavy German defenses in the area and the 36th Division now had its eyes on the stronghold of Bruyeres. With one of the division’s infantry regiments posed in support of the 442nd, and two other in defensive positions, the 442nd was to drive through Bruyeres towards Biffontaine with the ultimate goal of sweeping northward, buckling the German line. On October 15 the attack commenced with Franklin’s battalion in reserve. The 100th and 2nd Battalion began making their way through the German lines for two days before the 3rd was finally committed on October 17 for a battering ram attack against several of the major hills bordering Bruyeres. These tall and treacherously steep mounds resembled miniature mountain fortresses as German machine guns, artillery, and infantry all piled on the crests to fire down at the vulnerable Nisei. After nearly two days of combat for the hills the Germans began to fall back, leaving the town to Franklin and his fellow Nisei by the evening.

The victory at Bruyeres was not the end of the mission, however, so Franklin’s battalion began making its way eastward in hot pursuit of German forces. October 20 saw Franklin engaged in heavy fighting when they encountered stiff resistance along a railway two kilometers east of the town. Thankfully a quick surprise attack the next day allowed them to break through in conjunction with the 143rd Infantry Regiment of the 36th Division. After three more days of thick action, and the liberation of another major town, Biffontaine, the entire regimental combat team was relieved by the 141st Infantry Regiment of the 36th. Despite their already costly and wearisome combat time, the 442nd was not given long to rest before a vast emergency struck the 36th Infantry Division. While maintaining the 442nd’s advances, the 1st Battalion of the 141st Infantry Regiment had driven far beyond the rest of the regiment and been surrounded by German forces. With the whole regiment back on the line by October 27, the rescue launched immediately as Franklin and his battalion marched through the pitch black at 0400 out of Belmont into extremely thick forests and underbrush. The day did not begin easy as once German forces sighted the Nisei they began incessant artillery barrages, made even more deadly by “treeburst,” the fragmentation of wood and shrapnel that rained down upon the GIs when artillery burst at the forest canopy. It was incredibly deadly but was not the end of the German defenses. Sometime in the afternoon the enemy launched a counterattack against the 3rd Battalion using a Panzer IV and an armored car. With the harsh terrain and constant fire, it took nearly three hours to fight off the assault and disable the enemy armor. October 28 found the men driving onward suffering from heavy artillery fire sustaining massive casualties. The biting cold and rain made conditions no friendlier and by the end of the day they had moved a measly 1500 yards.

By October 29 the situation for the “lost battalion” was looking grim. The T-Patchers were low on supplies, food, and ammunition and no support could be given. The 3rd Battalion at this point was leading the charge towards the encircled Americans, jumping again to find the main enemy position. Despite a flanking maneuver, the battalion was unable to effectively draw enough German fire to open up a path through. It was not until M4 Shermans of the 753rd Tank Battalion finally arrived that the men could move forward. According to one account, the battalion faced “relentless small arms and mortar fire,” and was nearly completely pinned down. At this point, however, a lone Nisei of the 3rd Battalion attached a bayonet to his rifle and began yelling while charging up the hill all alone. Before long, the entire battalion joined in and the only banzai charge of the entire European theater erupted. With Franklin supporting these units, he either participated in or covered the men making this charge which ran straight through the enemy trenches, knocking out their guns and causing numerous Germans to surrender and flee. The fighting was lighter but still notable throughout the next day but around 1500 on October 30 a patrol from Franklin’s battalion made contact with the cutoff of 36th Division Troops. The “lost battalion” had been found.

While the 442nd had to remain in positions to secure the newly adjusted line, Franklin was fortunate to be taken off the line for several days due to an arthritic knee that had flared up during the attack. Minoru commented that this led to him “missing some of the fireworks on these hills,” however, he was able to rejoin by the time the 442nd was taken off the line for rest and refit on November 8. It was only another week and a half that Franklin and the regiment would stay with the 36th Division before becoming officially detached and moving down to Southern France in late November. Here they initiated what became known as the “Champagne Campaign” for the relatively lackadaisical defensive positions they stayed in along the French Alps. Minimal contact with Germans was made and for the most part, Franklin remained near Sospel in the middle of the occupied area.

It was not until April 1945 that the 442nd was back in action, this time under the 92nd Infantry Division in northern Italy. Lucky for Franklin he managed to miss the first week or so of combat as he had been given an extended furlough in Holland where he won a lot of money gambling (a habit he had picked up in the service). He did eventually return for the last weeks of the war as the 442nd made its massive motor march up through Genoa and onward until the German forces in Italy capitulated on April 29. For Franklin and his comrades, the end had come at last.

Franklin remained with the regiment throughout their extended occupation service in Italy, only coming home in July 1946. Returning home to see his family back in Seattle, albeit without their many belongings, was a rough existence and in his later testimony to the United States Congress he described the hardship he faced getting a job once he left the service. The loss of his family business and the earning power that had been brought on by incarceration and imprisonment created great financial strain on himself and his mother. Eventually finding a menial job as a stock clerk with another local grocery, he still found joy amongst his veteran buddies and became a lifelong member of the Nisei Veterans Committee, even attending their initial Memorial Day service at Lake View Cemetery in Seattle with many of his fellow 442nd veterans. Even with this friendship, he struggled to readapt to civilian life and in 1951, during the Korean Conflict, decided to enlist in the United States Navy where he would serve as a storekeeper for three years on the UNS Marine Lynx, the USNS Gen Hugh J. Gaffey, and the USNS Marine Adder. Eventually, he fully retired from naval service and married but never had any children of his own. One of the more important actions of his postwar life came in 1981 when he gave testimony to the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, describing in detail many of the injustices and struggles he and his family faced as a result of their forced internment during the war. His testimony, alongside many others, became key for the official apology issued by the U.S. Government in 1989 and the reparations given to thousands of surviving Nisei and their descendants.

Through his valorous military service and political action, Franklin gave back to his nation in more ways than one. He passed away in his Seattle home in 2007 at a comfortable 93 years of age, experiencing some of America’s darkest and most troublesome history firsthand. Through this Bible, carried with him across Europe and in some of his most harrowing moments, I hope to remember Franklin’s struggle, service, and sacrifice.

Image courtesy of Geri Nakao-Egeler and the Nisei Veterans Committee in Seattle

Image courtesy of Geri Nakao-Egeler and the Nisei Veterans Committee in Seattle